I have argued that the dislocations in the financial services sector in the next decade will include a rise in professional standards, a redefinition of what constitutes “value” and a need to increase the scale of financial advisory practices.

My next prediction is perhaps the most contentious. Within the next 10 years, there is a good likelihood that median compensation for financial advisors will drop significantly. Along with that reduction will come growing separation between the level of compensation for top advisors and that for everyone else in the field.

– Are advisors like autoworkers?

Ten years ago, workers on General Motors Corp.’s assembly lines who clocked a bit of overtime made $120,000 a year – twice what Toyota and Honda paid. GM’s autoworkers’ union had negotiated a “30 and out” clause that allowed workers to retire with fully indexed pensions at age 48 or 50. GM had job banks, so workers with seniority lobbied to get laid off so that they could collect 95% of their salaries indefinitely. Any rational person would have said this was nuts and that it couldn’t continue – and, of course, we all know how that story ended.

Certainly, today’s advisor compensation doesn’t approach that level of insanity. But, given the education and capital investment required to become a financial advisor, overall levels of compensation will almost certainly come under severe pressure.

– Advisor compensation today

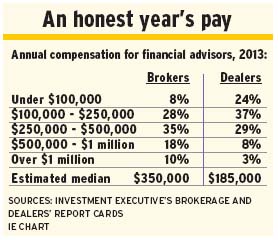

Research from Investment Executive‘s 2014 Report Card series indicates that the median compensation range for advisors working for dealer firms is about $175,000-$200,000; for brokers, the median range is $350,000-$400,000.

When looking at what’s reasonable regarding advisor compensation, there are no exact parallels. To get a frame of reference on market levels for compensation, I looked at senior executives in a financial role in the private sector. The recruiting firm Robert Half produces an annual salary guide that shows that someone holding this role in a mid-sized company would make around $150,000 a year, while in large companies, the number would be more like $175,000.

All of these individuals have substantial responsibility and experience, and many hold accounting designations. A reasonable observer looking at these salary ranges as a guide would conclude that the most the average financial advisor should earn is $150,000-$175,000 – perhaps half to two-thirds of what they make now.

Here’s another way to think about reasonable compensation for advisors. A faculty member of the MBA program at the University of Toronto, where I’ve taught for many years, asked what other people who provide financial advice make. The Robert Half compensation survey shows that private bankers earn between $57,050 and $93,000 annually, with a median of $78,000.

My colleague’s quick conclusion was that any advisor compensation above $90,000 is attributable to additional value on top of the advice that’s being provided. Which raises the question: what makes the market value of advisors so much higher than that of private bankers? (Note that this salary range almost certainly excludes the high-end private bankers at elite firms, who bring in business and are paid more – as are top-performing, independent financial advisors.)

– Factors that drive up compensation

There are four good reasons why advisors earn significantly more than is justified by the training they’ve received or the advice they provide:

1. Skill premium. If building a successful advisory practice was easy, many more people would enter the business, resulting in a price war that would quickly push down compensation. The key to success as an advisor requires a rare skill that has little to do with providing advice – and that’s the ability to attract clients. The reason why private bankers are paid much less than financial advisors is that bankers are fed clients, making those bankers an interchangeable commodity, and their salaries are subject to the forces of supply and demand. Advisors benefit from a “persistence premium,” as those who can’t attract clients leave the business (in some cases, adding to the supply of private bankers or financial planners available to work in bank branches, which depresses compensation in that channel).

The skill premium, when it comes to business development, isn’t unique to financial advisors. Look at the partners in any large accounting or law firm. The big earners are the rainmakers, those with the ability to bring in business. The scarcest commodity in almost any business is the ability to bring in clients, and that ability commands a premium. The question is: how big should that premium be?

2. Uncertainty premium. The traditional rule of thumb in the financial services sector is that fewer than one in four new salespeople make it to Year 3. When someone chooses to become a financial advisor, he or she is taking a big risk relative to a safe and stable job with a predictable salary.

For example, pharmaceutical sales representatives are similar to advisors in that they require in-depth knowledge, the ability to engage customers and strong selling skills. In 2013, the median compensation for pharma reps in the U.S. was US$125,000; US$155,000 for the pharmaceutical sector’s hottest industry, biotechnology. While comparable data doesn’t exist in Canada, a pharmaceutical company sales manager recently told me that total compensation (base, plus bonuses and car allowance) in Canada for reps with more than five years’ experience is $120,000-$130,000.

Part of the reason for the excess compensation for financial advisors, like the excess return in an equities portfolio, is a reward for the risk these advisors took in entering the business. Economists would argue that to enter any business, people need an expected value of future compensation (both financial and non-financial benefits that come from autonomy and doing something you love) that fully compensates them for the uncertainty they are facing.

3. Effort premium. On top of the risk of failure, being a financial advisor in the early and middle stages of building a business is exceptionally hard work – and, of course, many successful advisors continue to work hard after they become successful. Part of the compensation premium for advisors reflects how hard they work to build their business.

4. Risk premium. Anyone who runs his or her own business faces a greater risk of failure than someone who has chosen to be an employee. Even recognizing that job security for employees is not what it was, financial advisors who run their own business still face uncertainties and liabilities that an employee doesn’t have. And, again, this uncertainty needs to be reflected in the compensation that financial advisors earn.

Those four reasons partly explain why financial advisors deserve to make more than a private banker or a sales rep for a pharmaceutical company. But these reasons don’t account for the compensation premium that advisors have above senior financial executives.

This is the third instalment in a series on the future of the financial advisory business. Next: More reasons for the premium in advisor compensation and a course of action for maintaining premium compensation.

Dan Richards is CEO of Clientinsights (www.clientinsights.ca) in Toronto. For more of Dan’s columns and informative videos, visit www.investmentexecutive.com.

© 2014 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.