Advisory firms understand that newcomers to the industry require support from multiple stakeholders within the organization, including more experienced advisors. But those veterans are too valuable to their firms — and often too time-strapped — to handle training new talent from the ground up.

Still, as firms provide training for newer advisors, the addition of personalized guidance from a more experienced team member or industry mentor can speed the learning process.

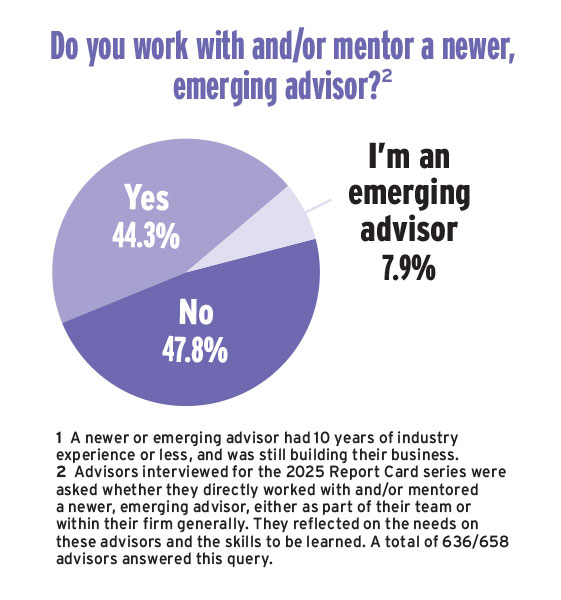

This year’s Brokerage Report Card included a new question on mentorship. IE asked all brokerage respondents, across the 14 firms assessed in the report, whether they actively worked with and guided newer advisors in the industry, or whether they were newer advisors themselves who needed support. (A newer advisor was defined as having 10 years of experience or less, and as someone who was still in the bookbuilding stage.) Of 658 advisors, 636 answered the question.

Since the average respondent in this Report Card was 51, with more than 20 years of industry experience, this question’s sample was predominantly made up of established advisors. Nine in 10 fell into that bracket, while only 50 of the respondents (or 7.9%) identified as developing advisors.

For the larger group of longtime advisors, the results were split on their mentorship activities. Less than half (44.3%) formally supported younger colleagues, while slightly more (47.8%) did not mentor or work alongside newer advisors (see pie chart).

How advisors feel about mentoring

The consensus among longtime advisors was that newer colleagues have an incredible amount to learn in their first few years, at the same time as industry competition is heating up — making mentorship crucial but also time-consuming.

“Emerging advisors need clients, and there’s a lot of competition. … They need to be able to differentiate their business from other advisors,” said an advisor with Leede Financial Inc. To do so, young associates first need to understand the business of established colleagues, the advisor added.

“Every mentor will have a [different] take on how to manage a business, from the compliance portion to the business side,” and it’s useful to get “an understanding of advisors’ [business] rationales,” said an advisor with iA Private Wealth Inc. in Ontario.

Since these emerging professionals need to also learn the ins and out of investment markets, how the back office works and which marketing and communication strategies are effective, designing a solid training program is tough.

Nonetheless, “A good coaching system [is a must],” complete with progress check-ins, said an advisor with National Bank Financial Inc. in Quebec. “If we leave the next generation of advisors alone, [they are] a little lost.”

One advisor with BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. in Alberta suggested these programs span several years, saying, “They need the[ir] firm to be patient with them. The first three years is for advisors to [get] help, learn and serve the clients.”

But dedicating several years to training new team members is a heavy lift, which is part of the reason nearly 50% of established advisors who answered the new mentoring question in this year’s survey said they don’t take part in the activity.

“I should be [mentoring],” said an advisor with Raymond James Ltd. In Ontario. “They [new advisors] need opportunity and time to build a business. Usually there is not enough time.”

Other advisors questioned the value of mentorship, and even the quality of new mentees.

“We are supposed to be independent-minded. There is no one right way to [run your business],” said an advisor with Leede Financial. I don’t ever want to mentor anyone,” they added.

An Edward Jones advisor in British Columbia said some developing advisors underestimate the work required to succeed. “I don’t work with any new advisors. … All the new ones want books given to them [and …] they don’t want to put in the work.”

Among many industry firms, advisors are free to choose whether they want to be mentors. For instance, Leede Financial president Steve Johnson said, “We don’t have a formal [mentorship] process that we would advertise to all advisors. Some jump at it and some just want to run their own business, which is fine too.”

He acknowledged that firms can share in the responsibility to help young advisors gain credibility. As his firm’s leader, Johnson has personally stepped up to join client meetings with rookies and support their practices, and he says, “It’s an important topic [to address] because I don’t think our industry is capturing the lion’s share of young people.”

While some established advisors feel junior colleagues should put in the work themselves, Johnson reflected on his experiences: “[For] myself and others who started in the industry a couple decades ago, or even further, we had less support. But there were easier ways to get your foot in the [door] and start making money to sustain yourself. Clients are [now] expecting some pretty sophisticated advice, and a lot of [processes] are only learned through exposure, mentorship and time.”

What new advisors need — and how firms are stepping up

The developing advisors polled in the Report Card understood it takes hard work to get started in the business. For example, an advisor in Ontario with RBC Dominion Securities Inc. said they’d built their book “from scratch,” calling the process “tough but rewarding.”

A common ask was for business-building help. “[I need] support in developing my business and help get[ting] my name out there,” said an advisor with CIBC Woody Gundy in Ontario. They appreciated “introductions to the right people” plus access to business coaching and lists of best practices. (That bank-owned brokerage was rated 8.3 for its “business development & marketing support” by its advisors, compared with 2024’s 7.9.)

At Odlum Brown Ltd., a newer advisor said they’d value insights from a sales manager, while another asked for more online marketing tools and help connecting with clients in their 30s and 40s who are amassing assets.

Warren Beach, chief strategy and business development officer with Odlum Brown, acknowledged the effort required when training newer advisors. “[That’s] an issue that all firms, including ours, have,” he said, noting his firm has increased its learning, development and coaching resources for younger advisors.

Since April, that firm has added both a new vice-president of sales and business development plus a new head of practice management — so there’s now “quite a focus on how we [can] help the emerging generation of [investment advisors] step into their career and role,” Beach said. (The firm was rated 7.2 in the business development category, unchanged from 2024, but these hires took place after IE’s data collection.)

Edward Jones is another firm that prioritizes new advisor support, said Jonathan Rivard, principal and Eastern Canada leader. That firm now has close to 140 multi-advisor locations, where two or more advisors work together and where mentorship is encouraged.

There’s also a consultation group advisors can access, he added, which includes experts like financial planners who help advisors develop in that area. Overall, “[We expect a] desire to give back and help each other, whether [advisors are] in the same office or they’re across the country on a Zoom call,” Rivard said. “That’s the energy and effort that’s made.” (This firm was rated 7.9 for its business development tools, the same as a year ago.)

At Nesbitt Burns, the “teaming program” is actively being reviewed, said Craig Meeds, head of Wealth Advice, Canada with BMO Private Wealth. It helps when individual advisors ask for help as they grow their businesses, “but as an industry, we have to do a better job of promoting the benefits of this [business] we work in,” he added. “We absolutely acknowledge that we need more talent in this business.”

Meeds appreciated the efforts of established advisors to date, saying, “We’re happy with our ability to attract, retain and develop talent,” but existing professionals have been helping a lot in that area. Even more structure will be placed around training new advisors to help solidify the bank’s best practices, team-building and educational programs, he added. (Nesbitt Burns was rated 7.5 for its business development tools, up from 6.4.)

Taking a similar step has been a necessity for iA Private Wealth, based on “a big demographic shift in the last two to three years,” said Adam Elliott, president and CEO of the firm. There, “The average [advisor] age has been coming down,” he added, saying the firm’s newcomers are “on teams or they start off as associates, and they then get licensed.”

Part of the draw for developing advisors has been iA Private Wealth’s varied book buying and financing options, Elliot explained. A new advisor can buy a book immediately or slowly buy equity over many years from a successor. The firm also has a practice management team, reporting to advisor and client experience executive Liz Lepore, “which does a lot of training sessions, some of them focused on developing advisors and [helping them] build a community.” (This firm was rated 7.3 for its business development tools, up from 7.0.)

Failing to offer that support is a risk, Elliot said, because the independent model “can be a bit lonely.” He wants to retain new advisors, he added, because “it’s the younger people who are taking over those practices and really leading them in some very innovative ways, pushing … all the time on the digital side.”