Jamie Golombek is the managing director, tax & estate planning, CIBC Private Wealth Management in Toronto.

With the clock ticking down to the March 1 RRSP contribution deadline, your clients are once again asking the perennial question of whether it still makes sense to contribute to an RRSP or whether there perhaps is a better route this year.

Individuals who voluntarily choose to set aside some of their current earnings by deferring present day consumption to a later period often look to three primary options: contribute to an RRSP, a tax free savings account (TFSA) or pay down debt.

At first glance, it appears that the answer is straightforward. After all, individuals with non-deductible high interest rate debt, like a credit card with a 20% interest rate, should clearly ignore saving for retirement as there is no surefire way to top that return in either an RRSP or TFSA.

But given the low interest rate environment of recent years, many Canadians are currently financing their homes using unprecedentedly low mortgage rates. In these situations, does it still make sense to pay down debt? Or is contributing to an RRSP or even a TFSA a wiser choice?

To explore this further, let’s take a look at the basic math you should review with your clients when guiding them toward an RRSP contribution, a TFSA contribution or a debt repayment on their mortgage, given limited funds.

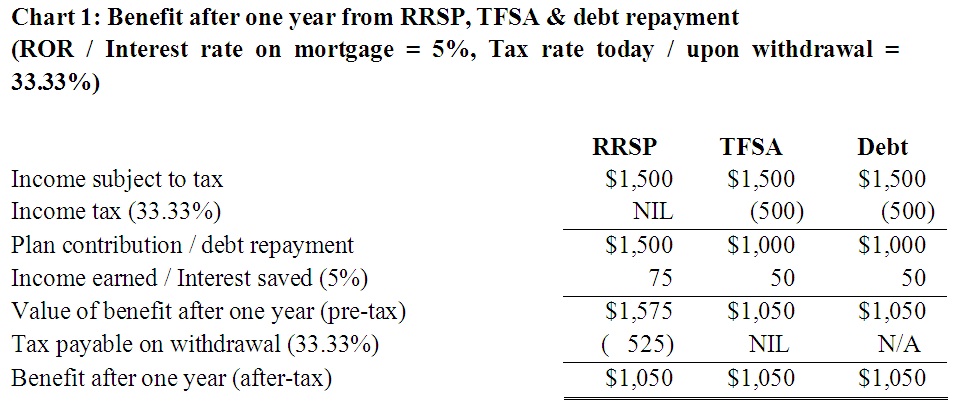

Assume that Isaac has $1,500 of excess pre-tax earnings not needed for current consumption and chooses to set aside this money either towards retirement savings in an RRSP or TFSA or by paying down his mortgage. We’ll assume his current tax rate is 33.33% and, for ease of illustration, Isaac expected to be at the same 33.33% tax rate upon retirement, when the RRSP or TFSA (should he choose one of those options) funds are withdrawn.

Isaac could choose to contribute the entire $1,500 to his RRSP, pay no current tax and only pay tax when the funds are withdrawn. Alternatively, after paying $500 (33.33% x $1,500) in current income tax, Isaac will be left with $1,000 of net after-tax cash flow that he can use to either invest in a TFSA or to make a principal repayment on his mortgage.

For this basic example (Chart 1), let’s assume that Isaac expects to earn a 5% average rate of return (ROR) on his RRSP or TFSA investment and has a mortgage with a 5% interest rate.

Chart 1 shows that no matter which solution Isaac chooses – RRSP, TFSA or debt repayment – he will have the same net benefit of $1,050. The lesson that can be learned here is that if Isaac’s tax rate is expected to be the same upon withdrawal as it is today, he should generally choose the solution with the highest rate (i.e. rate of return or debt interest rate), taking risk into consideration as discussed below.

Now, let’s shake things up by assuming that Isaac’s tax rate changes between the time of contribution and withdrawal and that the expected ROR on an RRSP or TFSA investment differs from the interest rate on his mortgage.

Assume Isaac’s tax rate today is still 33.33% but when he retires, he is expected to be in a lower tax bracket of 20%. Let’s also assume his mortgage interest rate is 3% and he believes that through equity investing he can generate 5% if he puts his money in an RRSP or TFSA for the long term.

Chart 2 shows Isaac’s benefit after just one year under these revised assumptions.

Editor’s note: This chart is no longer available.

If we take this example out 25 years, we can see (Chart 3) that the RRSP is the clear winner. This is attributable to two factors: the tax rate advantage resulting from a drop in Isaac’s tax rate from the year of contribution to the year of withdrawal and the ROR of 5% being higher than the 3% interest rate on the mortgage.

Editor’s note: This chart is no longer available.

A word to the rise: risk

The one potentially fatal assumption behind the maxim that it’s best to direct surplus earnings towards the solution (RRSP, TFSA or mortgage) with the highest expected rate of return or interest rate is that, in reality, return generally doesn’t come without risk.

For a five-year mortgage with a 3% interest rate, that’s pretty close to a sure thing for a five-year period; afterward there is reinvestment rate risk of interest rates rising when the mortgage is up for renewal. On the other hand, the rate of return from investing in equities through a TFSA or RRSP is far from guaranteed.

For a risk-averse investor who can’t stomach the ups and downs of the market or who has a significantly shorter time horizon than 25 years, the closest thing to a “risk-free” mortgage rate may be the Government of Canada bond yield, which this week was just under 1.5% for a five-year bond. For these clients, it may be safest to forgo an RRSP or TFSA contribution until their debt is paid off.

For the full report, please see: The RRSP, the TFSA and the Mortgage: Making the Best Choice.