Alberta’s election, the new Ontario Progressive Conservative (PC) government’s first budget and the court challenges to the federal carbon tax have dominated provincial finances so far this year. But under the radar, other significant stories are unfolding.

Quebec continues to rack up large surpluses; British Columbia and Nova Scotia are still posting smaller surpluses; New Brunswick is expecting its second consecutive surplus; and Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) forecast a return to surplus this year. And although Prince Edward Island hasn’t brought down a budget this year due to its election on April 23, the province returned to surplus last year.

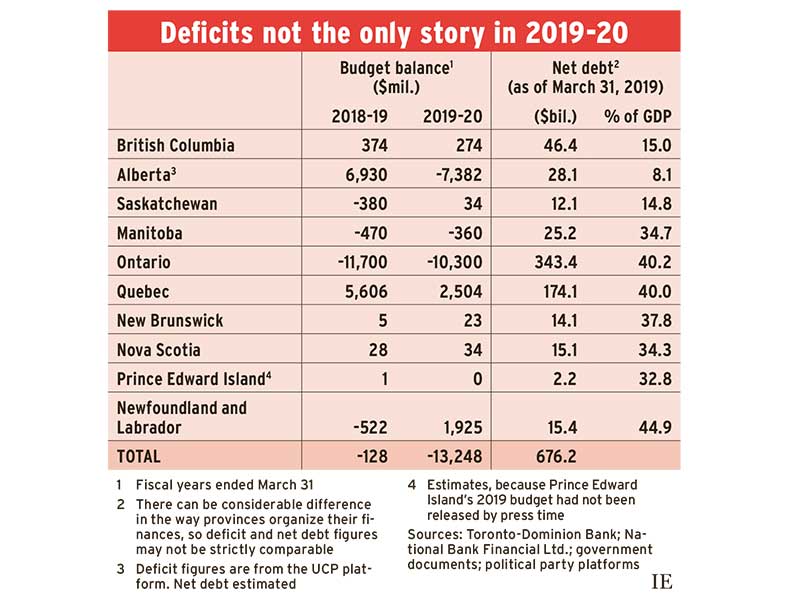

This is good news, but there still are three provinces with large, entrenched deficits. For fiscal 2019-20, ending March 31, 2020, Ontario projects a shortfall of $10.3 billion; Alberta’s is estimated to be $7.4 billion and Manitoba’s will be $360 million.

NL would have remained in the red, to the tune of around $600 million, if it hadn’t received a $2.5-billion windfall from the renegotiated Atlantic Accord. Although that money will be paid gradually over the next 38 years, all of it is being booked this year, producing a $1.9 billion surplus and reducing the province’s net debt to $13.8 billion or 40% of gross domestic product (GDP) for 2019-20, down from $15.4 billion or 44.9% of GDP for the fiscal year just ended. NL is projecting a deficit of $776 million in fiscal 2021.

The four deficit-bearing provinces (which include NL) stated that getting rid of their deficits will take until fiscal 2023 and that doing so will require continued economic growth and very restrained spending, neither of which is guaranteed.

The global economy is slowing and Canada’s is slowing along with it; the economic cycle is 10 years old already. Unemployment is low and interest rates are expected to continue climbing, even if more slowly than was anticipated a year ago. Trade wars and threats of further escalation on that front also are negative for economic growth.

On the spending front, Ontario plans to keep growth over the next four years to around 1.5%. Alberta’s newly elected United Conservative Party (UCP) is looking at a spending freeze. NL has expenditures dropping. Manitoba’s projections, which are for this year only, include a moderate 1.8% spending increase. B.C. was the only province to increase spending significantly, with a 4.5% rise forecast for this year.

The sole major tax change so far is Manitoba’s cut in the provincial sales tax (PST) to 7% from 8% as of July 1. Alberta’s UCP, elected on April 16, promises to cut the corporate tax rate to 11% from 12% in its first budget, with one- percentage-point cuts in each of the following three years to bring it down to 8%.

The dearth of tax cuts and big spending initiatives isn’t surprising, given the current slowing of the Canadian economy, says Marc Desormeaux, provincial economist at Bank of Nova Scotia in Toronto.

Sébastien Lavoie, chief economist at Laurentian Bank of Canada in Montreal, agrees but also senses a new determination to be fiscally responsible. He says many provinces “are acknowledging and accepting their profile.”

Governments, Lavoie explains, have acknowledged their challenges, such as aging populations. Furthermore, governments are accepting reasonable economic growth assumptions and are responding by limiting new spending, resisting major tax cuts and being cautious on capital expenditures and hiring. He includes Ontario in this camp, pointing to its proposed Fiscal Sustainability, Transparency and Accountability Act, which will require that all surpluses go immediately to debt reduction.

Overhanging all this is the fight over the federal carbon tax. Saskatchewan and Ontario have brought forward court cases challenging its constitutionality. Manitoba, New Brunswick and Alberta’s UCP stated they will do the same.

Here’s a look at the budgets in more detail:

> British Columbia. There weren’t a lot of new measures in this year’s budget, as the New Democratic Party minority government made most of its changes in its first budget after the May 2017 election, including measures aimed at cooling the Greater Vancouver Area housing market and instituting a payroll tax to replace the medical services premium. In this year’s budget, the B.C. child opportunity benefit replaces the early childhood tax benefit. Interest on B.C. student loans is eliminated, effective Feb. 19, 2019.

B.C. appears to be in excellent shape, with low debt and budget surpluses. But Lavoie is concerned that housing may be more depressed than the budget assumes, reducing the surplus or even resulting in a deficit.

> Alberta. The UCP platform includes cancelling the carbon tax, reducing the corporate tax rate to 8% from 12% over four years and introducing a “youth job creation wage” of $13 an hour for workers 17 years old and younger.

New premier Jason Kenney is going to be pushing hard for approval of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion and is threatening to cut off energy exports to B.C., as did the previous premier, Rachel Notley. A pipeline decision is expected in June.

> Saskatchewan. There is little in the way of new measures as the province returns to surplus. Very low oil and potash prices aren’t a drag on the economy anymore, but canola exports to China, a major customer, have been shut down.

> Manitoba. Although Manitoba has a substantial deficit, that government says the cost of the PST is justified because the measure should produce higher economic growth and offset lost revenue. Desormeaux considers this strategy a gamble. If the PST reduction doesn’t translate into stronger economic growth, the tax cut could take as much as half a percentage point off the net debt/GDP path.

The budget also extended tax credits to film and video production, small businesses, cultural industries and book publishers.

> Ontario. The PC government acted quickly after being elected in June 2018 to cancel the province’s cap-and-trade environmental program. The PCs also cancelled the increase in the minimum wage to $15, which was due to go into effect Jan. 1, 2019, and introduced a new refundable child-care tax credit. In this budget, the government didn’t go ahead with a promised one-percentage-point cut in the 12% corporate tax rate because the province is going along with the federal reduction in capital cost allowances. The province still plans a 20% cut in the middle-income tax rate, but not until the third year of its mandate.

> Quebec. This province introduced several targeted measures, including standardizing school tax rates, a rollout of full-day kindergarten for four-year-olds and incentives to keep seniors in the labour force.

> New Brunswick. The province has raised its minimum wage to $11.50 from $11.25 as of April 1, and also will ask Ottawa for a one-time “demographic weighted” health-care agreement that would reflect the province’s rapidly aging population.

> Nova Scotia. The budget included a new venture-capital tax credit, for those who invest in a venture-capital corporation or fund, as of April 1.

> P.E.I. On April 23, P.E.I. elected a 12-seat minority PC government, which promised to lower the small-business tax rate. The Green Party won eight seats, promising a $15 minimum wage. The Liberals (six seats) promised to reduce property taxes by 10%.

> Newfoundland and Labrador. With not much room to manoeuvre and an Oct. 23 election looming, the NL government delivered on its promise to end the temporary deficit- reduction levy and eliminated the auto insurance tax.