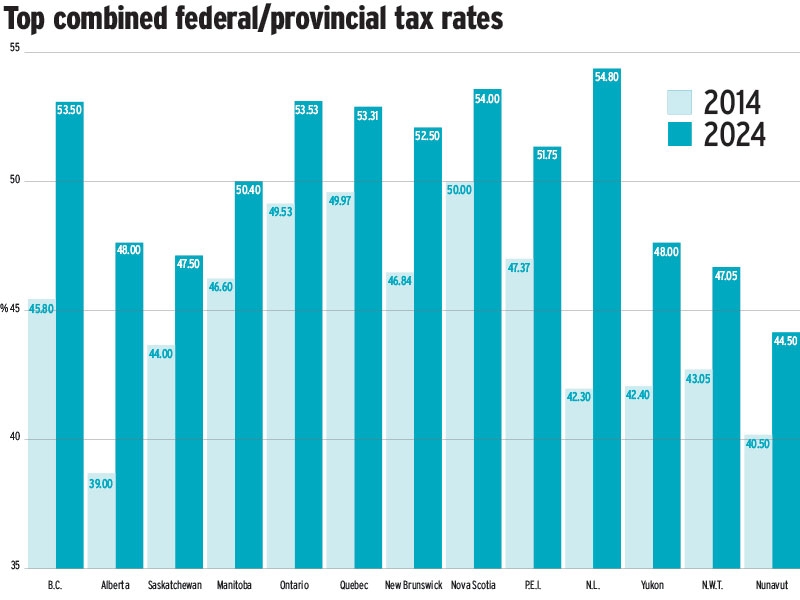

Canada’s highest earners in eight of 10 provinces will continue to pay more than half of what they make in income tax in 2024.

Only Alberta and Saskatchewan, as well as the three territories, have combined federal/provincial top tax rates below 50%. In 2014, no province or territory had a combined tax rate above that threshold.

Much of the increase in top combined tax rates over the past 10 years can be attributed to a hike in the top federal rate in 2016. That year, the Liberal government added a new top tax bracket and increased the top federal rate by four percentage points to 33%. The feds also decreased the tax rate on the second bracket by 1.5 percentage points to 20.5%.

However, some provinces also significantly hiked their top tax rates over the previous decade.

High-income earners in Newfoundland and Labrador face a combined federal/provincial rate of 54.8%, the highest in the country. That’s up from 42.3% in 2014, an increase of 12.5 percentage points. Most recently, in 2022, the province introduced three tax brackets and increased the top provincial rate to 21.8% from 18.3%.

British Columbia has a top combined rate of 53.5% for 2024, up by 7.7 percentage points from its rate of 45.8% in 2014. Between 2018 and 2020, the province increased the top provincial rate to 20.5% from 14.7%.

Over 2015 and 2016, Alberta moved from a flat provincial tax rate of 10% to graduated rates with a top rate of 15%, where the rate remains for 2024. The top combined federal/provincial rate in the province is 48%, up from 39% in 2014 — an increase of nine percentage points.

For 2024, Prince Edward Island decreased its provincial tax rates for its bottom three tax brackets and eliminated a 10% surtax. However, P.E.I. introduced two brackets and increased its top provincial tax rate to 18.75%, up from 16.7% in 2023. The province has a top combined tax rate of 51.75% for 2024, up from 51.37% last year and 47.37% in 2014.

In general, high tax rates disincentivize productivity and entrepreneurship, said Henry Korenblum, president of Korenblum Wealth Inc.in Toronto.

When top rates rise above 50%, they risk sparking a flight of talent to countries with lower tax regimes, such as the U.S., Korenblum said: “If you’re a high-income earner or a young professional, you might ask, ‘Is [Canada] where I want to establish my ties?’”

At the other end of the scale in Canada, top earners in Nunavut pay a combined rate of 44.5%, the lowest top combined rate. Among the provinces, Saskatchewan has the lowest top rate: 47.5%.

High-income earners can try to mitigate the effect of high rates through tax planning strategies, said Aaron Hector, private wealth advisor with CWB Wealth Management Ltd.in Calgary.

For example, many high earners with philanthropic interests make charitable donations because that will lower their tax liability. Both the federal government and the provinces offer donation tax credits. In addition, donations of appreciated publicly listed securities exempt donors from having to pay taxes on the associated capital gains, boosting the tax benefit for the donor.

However, high-income individuals must be mindful of proposed revisions to the alternative minimum tax (AMT), which allow only 50% of the donation tax credit to be applied against the AMT, down from 100% under the previous rules. Also, 30% of capital gains of donated publicly listed securities will be included in adjusted taxable income for the purposes of the AMT.

“It’s just one more thorough check you need to make [before a large donation] to make sure you’re not going to be exposing yourself to AMT — or at least going into it with your eyes wide open,” Hector said.

Click image for full-size chart

This article appears in the February issue of Investment Executive. Subscribe to the print edition, read the digital edition or read the articles online.

Uncooperative co-executor passed over by court

Case illustrates the risks of appointing multiple executors