Succession planning at wealth management firms across Canada has shifted over the years from patchwork efforts at the individual level to a more concerted effort from financial advisors and their firms — to ensure successful advisor exits and stability for clients.

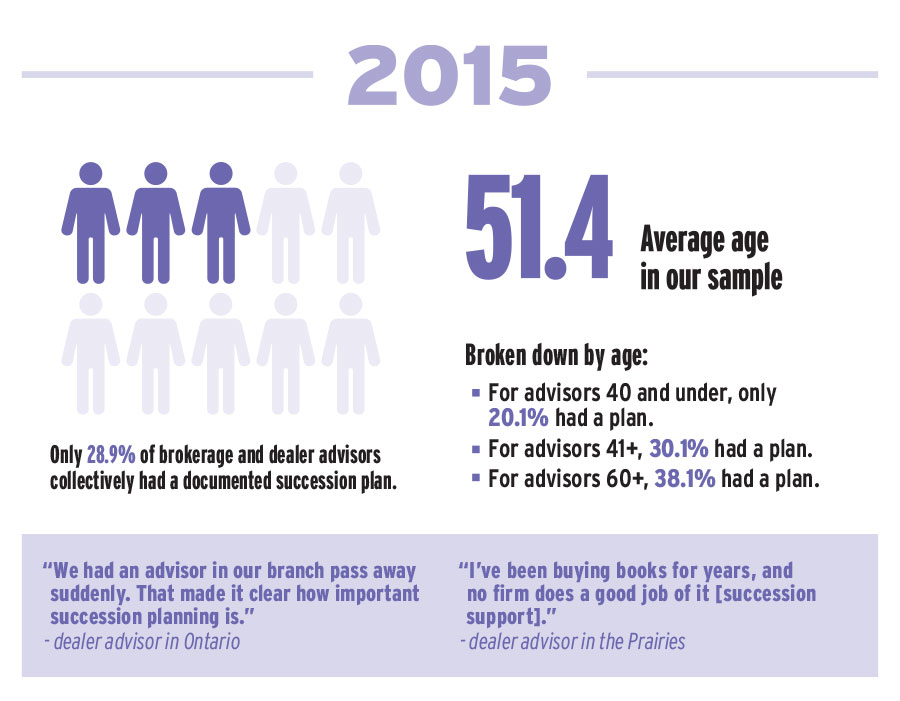

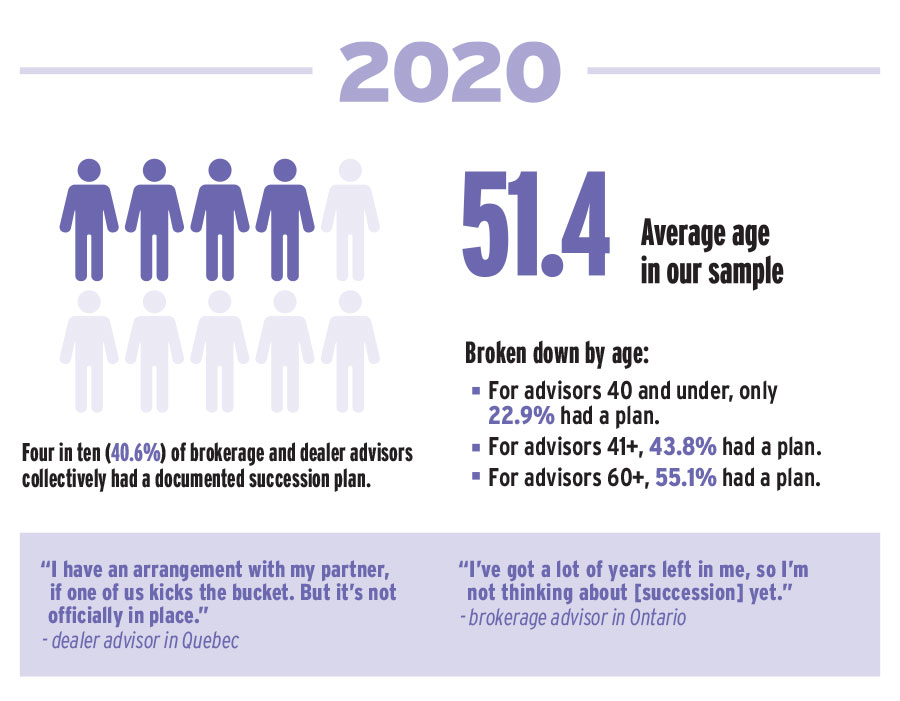

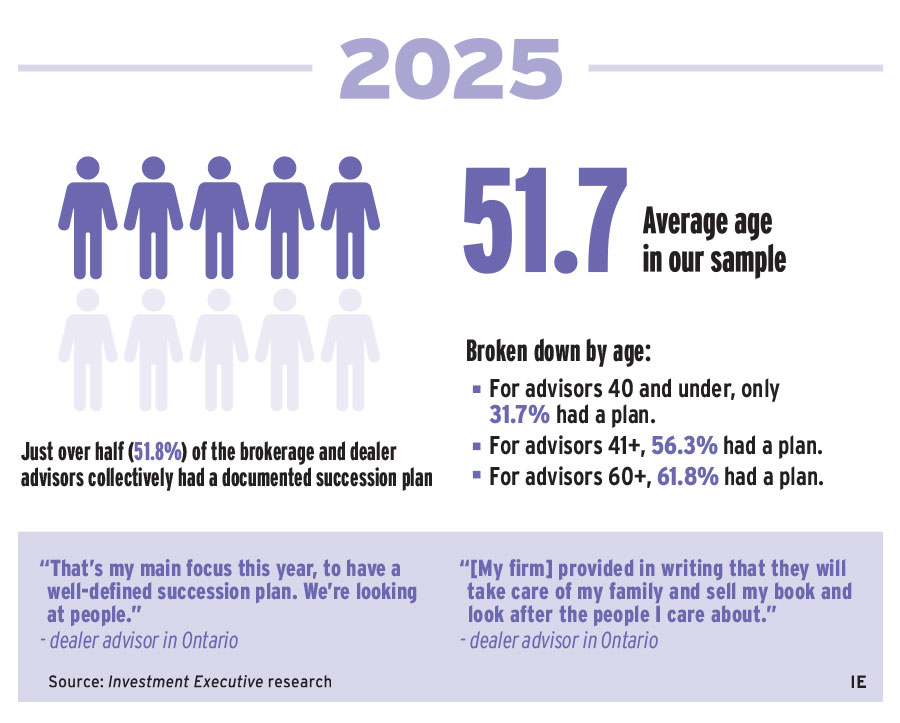

In Investment Executive’s (IE) 2025 Report Card series, roughly half (51.8%) of the advisors polled in the brokerage and dealer spaces said they had a documented succession plan. That compares with 45.9% who said the same a year ago, in those two channels — a notable rise over 40.6% in 2020 and 28.9% in 2015.

The age of the average advisor in our sample remained around 51 during this 10-year period.

What’s evolved is advisors’ thinking and how proactively firms are now taking steps to avoid the potential for orphan clients. “More advisors acknowledge the need to protect their clients and businesses, while firms also try to encourage advisors to prepare for the future,” said Katie Keir, research editor with IE.

“Advisors have varying levels of detail in their plans,” she added. “However, even among those who said they didn’t yet have a formal plan, there were many advisors who said they’re trying to connect with a successor and/or have started working on crafting an exit strategy. Others have had to rework their plans based on unplanned events.”

Keir’s research shows that, “More leaders each year are championing the benefits of teaming and peer learning, and are asking for insight into advisors’ challenges in the succession arena.” Still, it’s hard to determine the best avenue for firms to reach advisors who aren’t yet engaged on the topic.

Christine Timms, a retired advisor who’s written several handbooks for advisors including Transitioning Clients and the Retirement Exit Decision, said it’s good news that more advisors are creating succession plans than ever before, but the portion of advisors with a plan in Canada is “still not enough.” (No external sources were given access to IE’s specific research results, as the results are confidential until publication.)

“Even if you’re 40, you can get hit by a bus or have a heart attack, and everybody’s left in the lurch,” she said. “So, the numbers need to be better.”

This year’s study found that advisors aged 40 and under were less proactive than their peers. Less than one third (31.7%) said they had a documented plan, whereas 56.3% of advisors aged 41 and older said the same. For advisors 60 and older, the percentage exceeded 60%.

Still, all of these results beat those recorded 10 years ago. In the 2015 data for the brokerage and dealer spaces, even the advisors aged 60 and above had much room to improve, with only 38.1% saying they had a formal plan.

Looking back and ahead

When she retired in 2016, Timms said her firm had a template for succession plan contracts and a rough calculation process for estimating the value of a practice, which she called “very helpful.”

However, she said she wishes the firm had been able to provide a more accurate picture of the clientele she was supporting. Early into her career, she had already taken charge by creating her own ranking system of clients by household, assets, revenue and age.

“The firm didn’t have enough to tell me, even who my biggest producing households were and what the assets were,” said Timms, who had a 33-year run in the industry. “Through conversations with advisors, it’s my understanding that many firms have gotten better at analyzing practices, and so maybe they can see the risk a little bit better.”

Major gaps in business analysis processes would be a serious problem for the industry today, amid the ongoing great wealth transfer. It’s estimated that hundreds of billions of dollars have already changed hands, with another $120–$150 billion expected to transfer over the next two years. Advisors and their firms could either gain their clients’ heirs or lose them in the process.

The industry has also done a better job of encouraging team building in recent years, which has improved the succession planning process across the board, Timms said.

There are typically two types of advisor teams, she said. Mature advisors might team with a partner or bring on staff with different levels of experience. Either scenario can make for a successful legacy plan, so long as the older advisor is working with an individual or individuals who are younger than them and who will have a longer career runway.

By the time she retired, Timms had six people on her team of varying ages, including two associates who were her successors.

John Novachis, executive vice-president, advisor growth and succession at Investment Planning Counsel Inc. (IPC), said there were few resources available to exiting advisors 10 years ago. He’s been in the industry for more than three decades.

“Back then, advisors were left to their own devices,” Novachis said. “There was no support. There was no financing. There was a lack of successors. The kinds of transactions that were being entered into were very risky. The transaction cycles were very, very long. The amount of capital put upfront in a transaction [was little to nothing].”

Many advisor comments from IE’s 2015 Report Card series align with that view.

“I’d like to see more of everything. I’ve been buying books for years, and no firm does a good job of it [succession support],” said a dealer advisor in the Prairies. A brokerage advisor in Ontario said the succession program at their firm was “kind of vague. [It] only applies to a certain level of producer.”

Firms have “stepped up” and created more choice for advisors since, Novachis said, including offering financing programs to support peer-to-peer transactions and networking. He also pointed to more focus on team building to ensure a smooth transition of clients from an advisor to a successor.

“Today, there’s just more attention [and] structure,” he said. “Historically, book valuation was loosely based on a multiple to trailers, or recurring revenues, [which was] the most predictable and understandable quantitative metric for an advisor’s business. However, “There are various factors that influence the stability of recurring revenues,” including average client age, average client asset size and more.

“These factors are included when determining book valuation today,” Novachis explained, and there are also qualitative factors like how effectively an advisor works and uses technology, and “their audit and compliance rankings.” As a result, “The calculation of book values today is a blend of science and art.”

In the 2025 Report Card data, a brokerage advisor in the Prairies confirmed they were seeing progress with succession tools: “It is evolving, so … they are getting better.”

Novachis attributed this shift to the great wealth transfer, improved transparency across the industry and the Covid pandemic — which reminded firms that it’s important to be prepared for change.

Cautionary tales and concern about emergencies have long reinforced the value of planning within IE’s research.

“We had an advisor in our branch pass away suddenly,” said an Ontario dealer advisor in 2015. “That made it clear how important succession planning is.”

“When I made the move [to plan ahead], one of my big concerns was what would happen to me when I die and would my wife be taken care of,” said a brokerage advisor in 2025, also from Ontario. “[My firm] provided in writing that they will take care of my family and sell my book and look after the people I care about. … Also, my clients are going to be well taken care of.”

Timms said firm support can drive change. “All you need is for one firm to jump on making something better and to get a competitive edge for the other firms to decide, ‘Wow, I’m going to do that, or I’m going to maybe find myself losing some advisors to that other firm,’” she said.

What hasn’t changed for advisors

While greater resources are always appreciated, Timms said firms need to strike a balance between providing support and pushing too much on advisors who enjoy independence. “It’s not wise for a firm to be too heavy-handed, but it is wise for them to provide resources” for those asking.

The main reasons cited by advisors who’ve delayed succession planning have remained fairly consistent over the past decade. They have either felt like it’s too early in their careers or have still been looking for the right successor. Others have admitted procrastinating.

But when advisors don’t plan their exits as they approach the traditional retirement years, clients are likely to question what will happen once they’re gone, Novachis said. A 2025 survey from IPC found that while most Canadians expect advisors nearing retirement to have a succession plan, 83% of those who work with an advisor are worried about whether their advisor is proactively planning.

At least some advisors are clocking this. In 2025, one brokerage advisor in Quebec said, “We are asked for [future planning]. It’s important and secures the clients.”

Timms reminds advisors that the plan they initially create doesn’t have to be set in stone. “The person that you might want to take over your book when you’re 50 might not be the person you want to take over your book when you’re 60,” she said. With that in mind, there doesn’t always have to be 100% commitment, “unless you’re asking that person to join your team and work on your clients; then you need commitment.”

Click the images below for full-size versions.

This article appears in the November 2025 issue of Investment Executive. Read the digital edition or read the articles online.