The mid-December move by the U.S. Federal Reserve Board to raise the overnight rate to 50 basis points (bps)from 25 was long anticipated and, from the market’s point of view, a done deal by the time the increase happened. Three more increases are anticipated in 2017, which, if each is 25 bps, will put the Fed funds rate at 1.25% by the end of this year.

The Fed’s action, which is the first rate increase since 2006, portends major changes in fixed-income markets. The 34-year bull market in bonds – which began in 1982 with the actions of the Fed’s then-chairman, Paul Volcker, and Bank of Canada governor Gerald Bouey to break the back of inflation by zooming short rates up into the mid-teens – is ending.

Following the U.S. election and the expectation of increased U.S. government spending on infrastructure, together with major tax cuts, the yield on the two-year U.S. Treasury note rose to 1.26%, the highest since August 2009. The yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury bond rose to 2.58%, the highest close since September 2014.

In fixed-income, these yields are either a new world or a return to the old. With the exception of Switzerland’s sovereign bonds, all major European issuers have returned to positive yields on their 10-year sovereign debt. Within a week of the Fed’s move, Germany’s 10-year bunds offered 0.28%, the U.K.’s 10-year gilts paid 1.42%, and even Bank of Japan’s 10-year bonds have a 0.08% nominal yield to maturity. And this is only the beginning of what the market indicates is a global return to low to mid-single-digit returns for bellwether 10-year government debt.

Edward Jong, vice president and head of fixed-income with TriDelta Investment Counsel Inc. in Toronto, predicts that in three or four years, the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond will pay 3% and perhaps as much as 3.5% to maturity. Yet, even that modest forecast contains the seeds of a deeper bond price decline. The Fed announced after its September policy meeting that there might be only two rate rises in 2017. Now that the Fed has promised three increases this year, the 10-year Treasury bond’s yield could rise to 3% in just months and then surpass the earlier target, Jong says.

Uncertainty about the rate rises to come has pushed U.S. treasuries and other sovereign bonds deep into bear territory. As of the Fed’s mid-December move, the market had erased US$1.45 trillion in market value from the Bloomberg Barclays global treasury index, which tracks government bonds in developed and developing nations.

So far, market reactions to the Fed move, which eventually will be followed by other central banks, have slashed the value of long U.S. treasuries dramatically. In the first half of 2016, U.S. long treasuries produced a 19% return. That was reversed by the Fed’s mid-December move and market anticipation. For the 50 weeks of 2016 ended on Dec. 16, U.S. treasuries maturing in 10 years or more posted a 0.34% loss, wiping out all previous gains and essentially leaving the long treasury index flat. U.S. long bonds no longer offer security beyond return of capital.

What’s next? “The bond market is oversold in the short term,” says Chris Kresic, partner and head of fixed-income with Jarislowsky Fraser Ltd. in Toronto. The Fed’s move reflects the market’s view that deflationary concerns are over, he adds: “The bottom passed earlier in 2016. The Bank of Canada will resist raising its short rate, but will eventually be dragged into following the Fed.”

Looking ahead, Kresic figures that inflationary concerns, not growth, will drive interest rates. “There is declining growth in most developed markets,” he says. “Moreover, there are a lot of headwinds ahead. U.S. protectionist policies promised by Trump will hold down Canada’s [economic] growth and, hence, interest rates on our government bonds.”

However, a decline in the Canadian dollar could cause inflation to spike upward, and Canadian real-return bonds would thrive.

The recent sell-off of government bonds around the world was echoed in Canadian provincial and corporate spreads. In the rush to get out of government bonds ahead of an eventual move by the Bank of Canada to raise rates, many bond investors favour provincial debt. The provincial bond market has liquidity that corporate bonds can’t match, Kresic says.

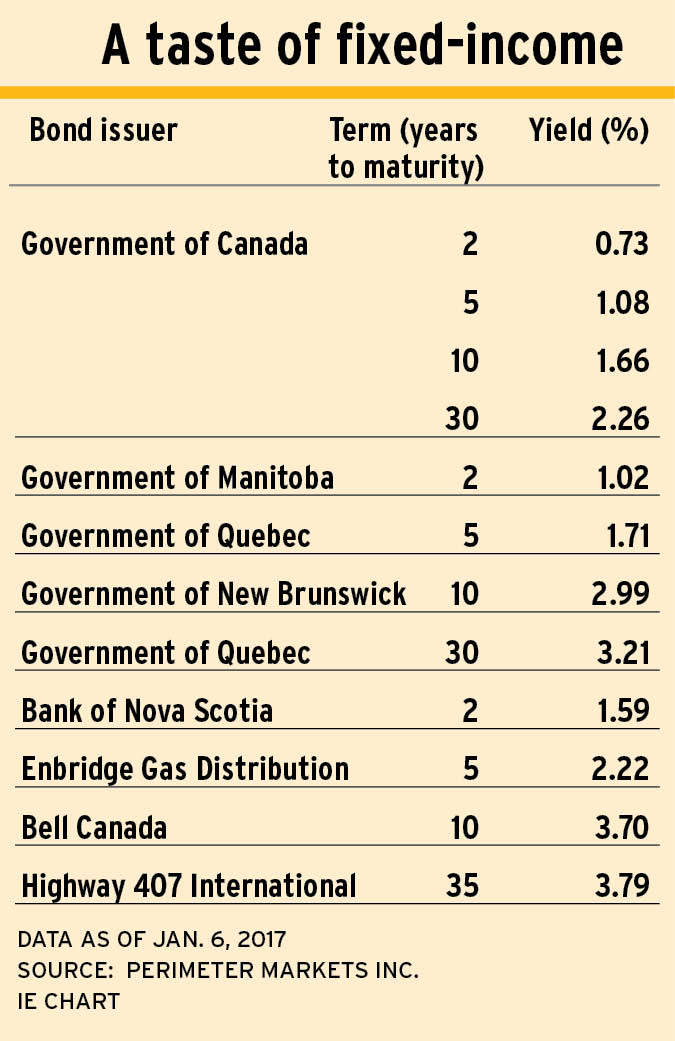

Provincial five-year bonds are yielding about 80 bps over Government of Canada bonds. Case in point: a Province of New Brunswick 1.55% bond issue due May 4, 2022, was recently priced to yield 1.99% to maturity.

Money also has moved into corporate bonds, with the upper end of 10-year, investment-grade debt priced at 204 bps over the 10-year Canada. For example, an IGM Financial Inc. 6.65% issue due Dec. 13, 2027, and rated A (high) by Toronto-based DBRS Ltd. was recently priced to yield 3.8% to maturity.

Global bond prices have tumbled. Yields on European and China’s 10-year and five-year government bonds rose as respective futures markets showed prices dropping by 2% for China’s government issues and 2.2% for eurozone government debt. Money is moving into U.S. debt because of the higher interest and, of course, the depth of the U.S. government bond market.

High-yield bonds surged even as global bond prices tumbled. U.S. high-yield mutual funds and ETFs had an inflow of US$3.75 billion for the week ended Dec. 14, 2016, according to Lipper. That was the third-largest weekly inflow in 2016 and the end of a four-week inflow to mutual funds and ETFs of US$6.7 billion. At the same time, year to date sales of high yield bond funds were US$10.55 billion of inflows compared with an outflow of US$5.89 billion over the same period in 2015.

The trend shows a clear rotation out of the investment-grade bonds that are being challenged by rising interest rates and into less rate-sensitive corporate debt at the high end of the risk scale. Investors clearly are electing to maintain income by choosing default risk rather than duration risk.

That’s evident from the Merrill Lynch High Yield Master II Index, which posted a 5% average return, down from 9% at the beginning of the year. “The perception is that there is less default risk in high-yield now,” says Adrian Prenc, vice president and portfolio manager with high-yield bond advisory firm Marret Asset Management Inc. in Toronto.

High-yield bonds remain an opportunity, says Charles Marleau, president and senior portfolio manager with Palos Management Inc. in Montreal: “They corrected after the U.S. [presidential] election, then rallied. The market perceives that high-yields have moderately strong fundamentals. Junk bonds will correct if interest rates continue to rise, but we would stick to shorter-duration high-yields to avoid carrying too much duration risk.”

For example, Marleau’s portfolio holds the oilfield services firm Canadian Energy Services & Technology Corp. (stock symbol: CEU) 7.375% issue due April 17, 2020, recently priced at $99; rated B minus by New York-based Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC and B by DBRS, the CEU bond offers a boost of 43 bps over the Government of Canada 1.50% issue due March 1, 2020, recently priced to yield 0.99% to maturity.

With expectations of rising interest rates in the U.S. and the eventual – indeed, inevitable – raising of interest rates by the Bank of Canada, a move from taking duration risk to accepting default risk is inevitable. After all, with rates rising globally, led by the Fed’s anticipated moves, major issuers’ sovereign long bonds will post red ink.

Sovereign debt provides guaranteed cash at maturity and thus appeals to institutional investors and banks that need government bonds for required capital. Other investors will migrate into subsovereigns, short governments and corporates.

Protecting income from capital loss is the essential strategy with the bond bear running.

© 2017 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.