Canada is surviving the oil price plunge well, despite being a major oil-producing country.

Although there’s economic pain in the oil-producing provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador, the feeling elsewhere is business as usual, with continued job growth, wage increases, solid retail sales and strong housing markets.

“This is a tale of two economies,” says Brian DePratto, economist with Toronto-Dominion Bank in Toronto. “People don’t realize how diversified the Canadian economy is.”

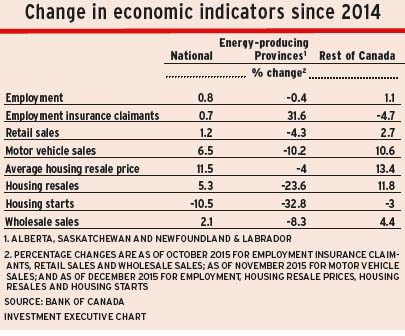

The divergence in the economic numbers for Canada’s two economies is startling, with employment dropping by 0.4% (from November 2014 to December 2015) and retail sales down by 4.3% (from November 2014 to October 2015) in energy producing provinces, but increasing by 1.1% and by 2.7%, respectively, in the rest of the country, according to the Bank of Canada (BoC).

The result is a situation in which overall Canadian real gross domestic product (GDP) growth is expected to be sluggish this year, but the economies of non-energy producing provinces are likely to expand faster.

For example, DePratto expects that in 2016, British Columbia’s GDP will grow by 2.5% and Ontario’s GDP by 2.2%, well above the 1.5% anticipated for the country as a whole. He foresees a 0.3% decline in Alberta’s GDP and a 1% drop in Newfoundland and Labrador’s, while the GDPs of Manitoba, Quebec, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island will hover around the national average. DePratto anticipates that Saskatchewan and New Brunswick will struggle with GDP growth of 0.9%.

This forecast puts the BoC in a difficult position because only parts of the country need monetary stimulus. However, any cuts to interest rates will be stimulative across the country. Thus, the overall situation calls for fiscal stimulus rather than monetary measures because fiscal stimulus can be targeted at particular regions.

In turn, this opens the door to questions about what will be in the upcoming federal budget. The new Liberal government stated before it was elected that it would run deficits to provide infrastructure programs to stimulate the economy – and infrastructure spending can be targeted geographically.

The resilience of much of the country is a result of the concentration of oil production in only a few regions, leaving other provinces in a position to enjoy the benefits of lower energy prices. Consumers have more money to spend after they fill their gas tanks, and expenses for many businesses have dropped – and those are just the first round of effects.

Any major shift in relative prices has multiple impacts, which kick in at different times and can feed off each other.

A major second-round impact will be an increase in non-energy exports. This comes from the drop in the value of the Canadian dollar (C$), which accompanied the drop in oil prices and which makes Canadian-manufactured goods and services more competitive, both in foreign markets and vs imports at home.

But additional sales will take time to materialize – usually, a year to 18 months.

Many companies have contracts with suppliers and can’t change to different suppliers until the current contracts end, says Frances Donald, senior economist at Manulife Asset Management Ltd. in Toronto.

Many Canadian companies also use currency hedges when purchasing foreign goods and thus haven’t benefited from the big drop in the C$. However, once those hedges have run their course, importers of Canadian goods and services are likely to increase orders so they can take advantage of the cheaper C$, says Donald.

Another factor that may have limited manufacturing exports to the U.S. is the depreciation in other currencies vs the U.S. dollar (US$), including Mexico’s peso, says Nathan Janzen, economist with Royal Bank of Canada in Toronto. That means U.S. buyers were finding cheaper goods in other countries other than Canada.

However, the C$ has weakened more than other currencies vs the US$ since July 2015, says Jimmy Jean, senior economist with Desjardins Securities Inc. in Montreal.

A further limiting factor – at least, in the short run – is that Canadian manufacturing was hollowed out in the 2006-14 period when the C$ was around US90¢-US$1.05. Thus, there isn’t the capacity to meet a surge in exports immediately. Companies can, of course, increase capacity, but they need to be convinced the demand will continue. Jean says we could see new investment starting later this year.

There aren’t the same limits on services exports – and that’s where economists foresee much of Canada’s economic growth in the future. Services account for about two-thirds of Canada’s economy, vs just 10% for manufacturing, notes Donald. She predicts that exports of services will become an “increasingly important driver” of economic growth.

There isn’t a lot of detail on services exports – and what exists isn’t current. However, Donald points to a study by the international affairs, trade and finance division, of the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which found an increase in Canadian exports of services to $75 billion in 2011 from $20 billion in 1990.

The biggest exports were for commercial services, including those related to management, computer and information technology, architecture, engineering, insurance, research and development, audiovisual and communications, as well as royalties and licence fees. These exports totalled $42 million in 2011.

There already is anecdotal evidence of increased foreign demand for Canadian services. DePratto points to reports of higher U.S. and U.K. sales by Montreal-based information technology company CGI Group Inc., for example.

There also were significant Canadian exports of travel and transportation services of $17 billion and $13 billion, respectively, in 2011.

Note that the travel data includes spending by tourists visiting Canada. There was a 7.8% increase in foreign visitors to Canada in 2015 after four years of little change. On a relative basis, Prince Edward Island was the major beneficiary of increased tourism; but, in terms of numbers, B.C., Ontario and Quebec had many more tourists.

Transportation services includes railways and trucking. Volumes were weak last year, but are expected to increase with more Canadian exports to the U.S.

Another impact of low oil prices is that workers are leaving oil-producing provinces and moving to regions in which there are more jobs. In the third quarter (Q3) of 2015, net migration into Alberta dropped to 1,234 people from 8,137 in Q3 of 2014. For the same periods, net migration into B.C. increased to 6,315 from 3,632; for Ontario, 1,207 people migrated into the province in Q3 of last year vs an outflow of 3,226 in Q1.

These population shifts should continue and, indeed, probably will accelerate, says Donald. That has implications for both the labour and housing markets.

Donald points out that these population flows will limit how high the Alberta unemployment rate rises because there will be fewer people looking for work in that province.

But the migration trend also is likely to accelerate the drop in house prices in the provinces in which people who want to leave when they put their houses up for sale.

© 2016 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.