If you’re looking to monetize your knowledge of corruption and malfeasance in the investment industry, you could have your chance soon.

The Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) is proposing to introduce a new whistleblower program that would reward tips leading to enforcement action and major monetary penalties.

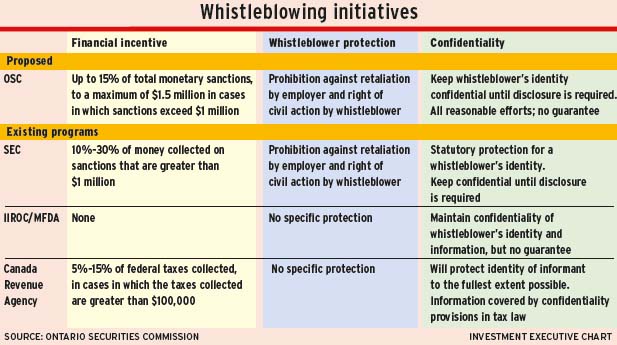

The OSC released a long-awaited consultation paper on Feb. 3 that sketches out a vision for a program to encourage investment industry insiders to report serious misconduct. A key feature of the program is that it would provide a financial incentive for insiders to come forward with valuable information. In fact, the OSC is proposing that whistleblowers be eligible to receive a reward for their information, up to a maximum of $1.5 million.

The actual size of any award would be at the OSC’s discretion, but the program envisions rewarding tipsters only in cases that generate at least $1 million in monetary sanctions. The program could pay out up to 15% of the total value of those sanctions.

The program’s primary goal is to alert the OSC to misconduct that the regulator likely wouldn’t discover otherwise, says Tom Atkinson, the OSC’s director of enforcement. The OSC has researched these types of programs extensively over the past few years, he adds, and has come to the conclusion “that this is an important tool to have in our arsenal.”

Whistleblowers can provide highly specific information that helps to focus and expedite investigations, Atkinson notes. Also, the mere existence of a whistleblower program that provides a financial incentive may encourage more self-reporting because a firm may rather admit a violation and claim credit for co-operation before an employee reports it.

The OSC proposal differs notably in two key respects from the whistleblower program that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has been operating for several years:

– The SEC program offers the potential for higher financial rewards, as that regulator will pay out up to 30% of the money collected in an enforcement case – and there’s no upper limit on the size of a reward. In fact, the SEC’s largest whistleblower award payout to date – US$30 million – was handed out last year.

– The OSC is proposing to fund its whistleblower payouts with sanctions collected in other cases or even from its general revenue. Unlike the SEC’s program, the OSC would not have to collect the money from the sanctioned firm or individual to pay a reward.

This funding is key to the OSC proposal, given the regulator’s notoriously poor collection record. According to the OSC’s latest annual report, the collection rate has declined to just 2.9% in fiscal 2014 from 7.8% in fiscal 2012. Atkinson believes the OSC’s collection rate is improving because the types of cases that result in large, unpaid sanctions orders are increasingly taking the quasi-criminal route as the OSC pursues jail time for these offenders.

Nevertheless, Atkinson concedes, providing a credible financial incentive to a prospective whistleblower would be difficult if the OSC’s poor collection rate undermines a payout. That’s why the OSC is proposing this approach to funding these awards. Indeed, for a whistleblower program to succeed, the rewards have to be meaningful and attainable.

Although the SEC protects the identity of a whistleblowers that receive payouts, the U.S. regulator does announce publicly when payouts take place, which lets potential whistleblowers know that these rewards for providing incriminating information are genuine.

According to data from the SEC’s Office of the Whistleblower, more than 10,000 tips have been received since the program was introduced in late 2011. Moreover, the total number of tips has grown every year and reached more than 3,600 in 2014, up by more than 20% since the program started.

During that period, the SEC has concluded 570 enforcement actions that generated at least $1 million in sanctions, the threshold for a possible whistleblower award. The SEC has handed out rewards to 14 whistleblowers, nine of which came in 2014. The SEC also denied claims from 19 whistleblowers and has denied 196 claims from one person who since has been declared ineligible for any award after filing several frivolous claims.

Although the SEC’s program appears to be gaining traction, there are potential pitfalls to the prospect of paying whistleblowers. Last year, regulators in the U.K. decided against providing financial incentives to whistleblowers amid concerns about moral hazard and worries that this practice could motivate malicious or opportunistic reporting, inspire efforts at entrapment and undermine the prosecution of cases that go to court if a whistleblower stands to gain financially.

Regulators in the U.K. also worried about the public perception of a regulator possibly paying out large sums of money to already well-paid investment industry insiders for blowing the whistle on misconduct, which, they noted, is something industry personnel should be doing anyway as part of their duties.

Yet, the OSC’s research found that most whistleblowers aren’t seeking a windfall when they tip off regulators, Atkinson says. Rather, the prospect of a payout provides some assurance that they won’t suffer financial hardship for doing the right thing.

The primary objection to the program, Atkinson anticipates, is the fear that regulatory incentives could undermine internal reporting mechanisms. This concern was raised when the OSC first suggested introducing a whistleblower program in 2011.

At the time, investor advocates were in favour of the idea. But one issuer, George Weston Ltd., warned that regulators paying for information would hurt companies’ efforts to create internal compliance systems. However, Atkinson points out, 80% of the whistleblowers that have received awards from the SEC previously had voiced their concerns internally and were ignored.

Still, these worries are the kinds of issues the OSC must grapple with as it decides whether to adopt a whistleblower program and, if so, how the program should operate. The consultation paper raises fundamental questions about the design and operation of the program, including: what should the criteria be to make whistleblowers eligible for a reward; should they be able to remain anonymous; and should people involved with misconduct be able to claim rewards?

The OSC’s proposed approach is open to debate – and could well be changed before the OSC presents a proposed rule to implement the program. The OSC’s proposals are out for comment until May 4 and Atkinson estimates the program could launch in early 2016, given the time required to make the rules and seek the necessary legislative changes.

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.