The outlook for the global economy in 2013 rests largely on the U.S. The big question is how U.S. companies will react to the last-minute deal to avoid the so-called “fiscal cliff” that was worked out in Washington, D.C., on New Year’s Eve.

If company executives trust that the deal is real and that the Republicans and Democrats soon will negotiate the rest of what’s needed for a credible deficit- and debt-reduction plan, executives could start investing in their businesses, including purchasing machinery and equipment, making acquisitions and hiring workers.

But if company executives think the deal is just a stopgap measure and the two political parties will continue to wrangle, they will continue to sit on the mountains of cash on their balance sheets and gross domestic product (GDP) growth will remain sluggish at around 2%.

As things stand now, only a small step has been taken. The major negotiations on spending cuts remain; if they aren’t resolved soon, more crises will erupt as other deadlines near. The debt ceiling must be raised in late February and the automatic spending cuts that were scheduled to kick in on Jan. 1 were delayed for only two months.

Most strategists and fund portfolio managers expect the austerity measures agreed upon will produce a fiscal drag of 1%-1.5% – a manageable amount of austerity that should keep the U.S. economy growing at 2%-2.5%, given the private sector momentum. As a result, many are generally overweighted in U.S. equities. But opinions vary.

Nandu Narayanan, chief investment officer with Trident Investment Management LLC in New York and manager of a number of funds sponsored by CI Financial Corp., expects only 1% growth in the U.S. this year. He wouldn’t invest there right now.

Ross Healy, chairman of Strategic Analysis Corp. in Toronto, thinks the U.S. economy will tread water, with essentially no growth. But, he adds, because the U.S. dollar (US$) is the world’s reserve currency – and could be for some time – some U.S. companies will do well. He would buy some U.S. stocks if the markets have a significant correction this year, as he expects.

On the other hand, Jean-Guy Desjardins, chairman, CEO and chief investment officer (CIO) with Fiera Capital Corp. in Montreal, thinks U.S. GDP growth could be 3.5% this year. That’s based partly on his assumption that most of the anticipated measures in the final debt-reducing deal will be back-loaded and not come into effect for three years or more. But Desjardins also is assuming strong exports because he believes the decline in the US$ has made the country’s goods much more competitive than most people realize. Thus, he expects the U.S. to increase its share of sales in many markets.

Other portfolio managers who think the U.S. could surprise on the upside include Peter O’Reilly, head of the global equities team with I.G. Investment Management Ltd. in Dublin; David Andrews, director of investment management and research with Richardson GMP Ltd. in Toronto; and Martin Hubbes, executive vice president, investments, and chief investment officer with AGF Investments Inc. in Toronto.

Assuming the U.S. GDP grows by at least 2%, global growth is expected to be around 3.5%, up from 3% in 2012. Most of the pickup is coming from the emerging markets, most of which were successful in reducing inflation to manageable levels last year through tighter monetary policy and are now lowering interest rates. Europe is universally expected to be weak. Portfolio managers don’t expect much out of Japan, although there is a slim possibility that its new government may be able to kick-start that economy.

Despite the relatively moderate global growth forecast – 4.5%-5.5% had been the norm before the credit crisis – most strategists and portfolio managers suggest being overweighted in equities, mainly because of the low interest rates being maintained by central banks in the industrialized world to stimulate the global economy.

With negative real returns for government bonds and investment-grade bonds often barely matching the yields on good dividend-paying stocks, the main purpose of fixed-income in portfolios is diversity and safety.

There is the option of high-yield bonds to get extra return. Some portfolio managers, such as Norman Rashkowan, executive vice president and chief North American investment strategist for Toronto-based Mackenzie Financial Corp.‘s Maxxum funds, are currently enthusiastic about high-yield bonds. Many Maxxum funds, Rashkowan says, include bonds from “the better part of high yield: B to BBB rated.”

However, many portfolio managers avoid high-yield bonds and few strategists recommend that these assets make up more than 10%-15% of retail investors’ portfolios. High-yield bonds have more risk than most non-speculative stocks and don’t offer the possibility of capital appreciation.

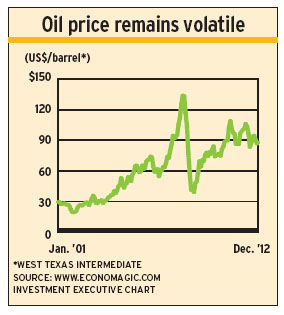

Further complicating financial planning is the challenge of finding equities that are likely to appreciate in a moderate-growth environment. Even if you pick the right sector or region, not all the stocks in it will go up because it isn’t easy for companies to keep earnings growing. To do so, they need strong management that makes good decisions and executes well. That includes resources companies because oil, natural gas and mining prices aren’t expected to jump much higher this year. (See page B10.)

This makes the current environment a stock-picking one. As the text that follows and the other stories in this report show, there are gems in places with little or no growth, such as Europe and Japan, but the risk of paying too much in apparently good markets also exists because some valuations have risen too high.

Here’s a look at the major regions:

– THE U.S. Politics and its effect on business and consumer confidence will continue to be the major factor in this market.

Business executives not only have to decide if they trust that further measures needed to deal with government deficits and debt will be reasonable and not pull the rug from under them; they also are contending with increasing regulation and the threat of more to come. (See page B18.)

American consumers got a tax break with the New Year’s Eve deal on the fiscal cliff, which removed the increase in their tax rates that was scheduled to come into effect on Jan. 1. But consumers will be uneasy until they know what spending cuts will be agreed upon and how they will be affected by those measures.

@page_break@Nevertheless, the U.S. is the most resilient, flexible and innovative economy in the world, and it frequently exceeds expectations. In addition, the emergence of shale natural gas and oil deposits will make the U.S. self-sufficient in energy in, probably, another 10 years, which will free the country from large import bills for its oil needs.

Shale gas already has driven down the price of natural gas, making it more feasible to build production facilities in the U.S. – and even move some offshore production capacity back home. This trend also can be attributed to rising wages in emerging countries such as China, which was already narrowing the gap between its costs and costs in the U.S., explains Charles Burbeck, co-head of global equity portfolios at UBS Global Asset Management (UK) Ltd. in London.

“Many U.S. industries are now cost-competitive,” agrees Drummond Brodeur, global strategist with Signature Global Advisors, a division of CI Financial in Toronto. Land costs in China, he adds, are now higher than in the U.S.

Well-capitalized U.S. banks should do well as the U.S. housing market picks up – in contrast with Canadian banks, which aren’t expected to outperform this year due to fewer bank loans in the face of a cooling domestic housing market and overleveraged consumers. (See page B8.)

The upside potential for U.S. banks is one of the strongest convictions of Stéphane Marion, chief economist and strategist with National Bank Financial Ltd. in Montreal, who has recommended that clients buy a U.S. bank-based exchange-traded fund.

There’s enthusiasm for U.S. consumer discretionary stocks, as the improving housing market will mean increasing purchases of home-related goods and services.

And U.S. industrials and information-technology stocks are being overweighted by portfolio managers who’ve become more confident that global growth is picking up.

– EUROPE. There isn’t a lot of enthusiasm about Europe, with most portfolio managers expecting the region to remain in recession until at least the second half of this year.

Narayanan and Healy are particularly pessimistic, and neither would invest in Europe. And neither Desjardins nor Lloyd Atkinson, an independent financial and economic consultant in Toronto, have any interest in the region, although Desjardins would buy euros because he thinks that currency’s value will rise as Europe makes progress on its fiscal and banking issues. That would provide a nice currency gain in Canadian dollars.

Most other portfolio managers also are underweighting European equities, but there are some enthusiasts. Burbeck and Hubbes – as well as Don Reed, president and CEO of Franklin Templeton Investments Corp. in Toronto; and Jurrien Timmer, director of global macro and portfolio manager with Fidelity Management & Research Co. in Boston – are overweighting Europe based on the low valuations to be found there and the possibility of somewhat better than expected economic data.

In Hubbes’ view, a lot of bad news has already been priced into European stocks.

“There’s a lot of value there,” agrees Reed, noting the very cheap valuations, whether measured by the ratio of price to earnings, cash flow or book value.

Portfolio managers particularly favour global European companies that aren’t dependent on the European market yet their stock prices have plunged because the companies happen to be located there.

European financials also are popular picks. Reed started investing fund assets in Italian, French and British banks that had completed recapitalization in mid-2012; he’s holding off on the Spanish banks until they’re recapitalized. Burbeck favours Paris-based BNP Paribas SA.

Leo de Bever, CEO and CIO of Alberta Investment Management Corp. in Edmonton, also is interested in certain firms in Europe – particularly more established franchises with higher dividends for which clients are prepared to pay.

– JAPAN. This country’s economy hasn’t gone anywhere for 20 years and suffers from deflation. Japan has the oldest population in the world but doesn’t welcome immigrants. Much of Japan’s economy is protected and uncompetitive; even the exporters, which had provided what little momentum that had existed, are losing market share against lower-wage competitors and are struggling with the current high value of the yen. Government debt is more than 200% of GDP and is manageable only because most of it is held by domestic investors.

However, some portfolio managers think the newly elected government has a chance of getting Japan’s economy moving. Plans include fiscal stimulus through government spending and looser monetary policy aimed at both weakening the yen and getting rid of deflation by targeting 2% inflation instead of 1%.

This possibility has some portfolio managers, including Burbeck, Narayanan and O’Reilly, eyeing Japan with interest. Hubbes also is interested but cautious: it will be a few months, he says, before we see if the economy is going to pick up steam.

There is a caveat to investing in Japan: although portfolio managers can see its market doing better, they’re having trouble finding specific companies to invest in. The big-name global companies that used to be a good way to get exposure to Japan’s market have been badly hurt by the rise in the yen. Nevertheless, portfolio managers specializing in Asia are finding interesting possibilities. (See page B14.)

– EMERGING MARKETS. With economic growth picking up, most portfolio managers are overweighted in these regions – particularly Asia, but also Latin America.

But not everyone is on the bandwagon. Hubbes, for one, thinks the expected increased economic growth is already priced into these markets, so he is slightly underweighted in emerging markets.

There are two ways to invest in emerging markets. Clients can buy the local equities or invest indirectly, through companies that benefit from growth in these regions, such as multinationals, exporters and resources companies.

The last group appeals to a lot of portfolio managers, including de Bever. Legal systems, accounting rules, regulations and corporate governance make it hard to be sure what risks clients may be running by owning equities in emerging markets.

There are signs that China’s economic growth is picking up after last year’s slowdown, which was induced by inflation-fighting policies. It also is widely believed that the new government – the country just completed its once-in-a-decade leadership change – has a pro-growth approach and won’t hesitate to introduce fiscal stimulus if needed. (Other emerging countries also are recovering from a relatively weak 2012, due to their inflation-fighting efforts.)

Although China’s economic growth is expected to be better this year, it’s not expected to return to the red-hot pace of the past decade. Most analysts believe the country is making the transition toward growth of 7%-8% as the economy shifts to more reliance on consumer spending and less on infrastructure building and exports.

That lowers the possibility of further sustained increases in oil and mining share prices, as demand from emerging markets – particularly China – is the driver of resources prices.

Desjardins disagrees that China is moving toward slower growth. While that will happen, he says, it will take 15 to 20 years, so he is optimistic about the outlook for resources.

However, most portfolio managers are market-weighted in resources, with a bias toward energy, for which demand will grow as more emerging-market consumers own cars. In general, portfolio managers prefer countries with strong domestic consumption and without heavy reliance on exports to the U.S. and Europe. In Asia, that means countries such as Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia rather than Taiwan and South Korea. (See page B15.)

Among other emerging markets, Mexico is considered particularly interesting. Timmer says costs there now are lower than in China, and Raschkowan agrees. There also are possibilities in Eastern Europe and Africa.

© 2013 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.