THE GOVERNMENT’S DECISION TO lower the minimum withdrawal factors for registered retirement income funds (RRIFs) has been applauded by both the Canadian financial services sector, which had been lobbying for the change for years, and by tax experts, who argue the lowered minimum rates will give seniors more opportunity to preserve capital in retirement.

“Anything that encourages seniors to save over the long term is good,” says Wilmot George, vice president of wealth planning with CI Investments Inc. in Toronto. “The lower RRIF minimums help to ensure that, over time, retirees will be able to take care of themselves.”

However, financial advocacy groups such as the Toronto-based C.D. Howe Institute say that the changes did not go nearly far enough. The institute suggests the government should consider lowering RRIF withdrawal minimums even further or eliminate the withdrawal factors altogether. Because assets in a RRIF will be taxed eventually – at the latest, when RRIF accountholders (or their beneficiaries) die – the government should allow RRIF accountholders complete control regarding how much or little they withdraw while they’re alive.

“It really doesn’t matter when the government collects the taxes [on the assets in the RRIF],” says Bill Robson, president and CEO of the C.D. Howe Institute. “The government is immortal; it will collect the taxes one day. But [the timing of withdrawals] does matter for the taxpayer, who is mortal, [and for whom] the timing of the tax matters a great deal.”

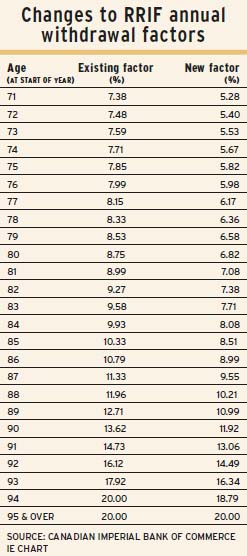

New RRIF minimums, first proposed in the 2015 budget and now enacted into law, were lowered by almost 30% compared with the previous withdrawal schedule. For example, for a 71-year-old individual, the withdrawal rate now is 5.28%, down from 7.38% in the previous schedule of withdrawal rates. According to a table from the budget documents, $100,000 in a RRIF at age 71 would be drawn down to only $44,000 by age 90 if using the new minimum withdrawal factors, compared with $30,000 if using the previous rates.

Updating of the RRIF minimums, which had not been changed since 1992, was overdue. Canadians are enjoying longer lifespans, but that also means they risk outliving their savings in retirement. Meanwhile, interest rates have remained low, making the generation of growth without taking on undue risk difficult for retirees. And costs, particularly those related to health care, continue to rise.

“People aren’t getting the same return from their RRIFs as they used to,” says Jamie Golombek, managing director of tax and estate planning with the wealth advisory services division of Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce in Toronto.

The C.D. Howe Institute advocates the elimination of the withdrawal factors altogether, contending that while the lower rates certainly are welcome, they already may be out of step with shifting economic realities – including lower portfolio yields. Barring the updating of rates every year, which may not be practical, getting rid of the rates altogether should be considered, Robson argues: “Retirement planning would become a lot more straightforward.”

Toronto-based CARP, the national advocacy group for retirees, also argues that RRIF withdrawals factors should be withdrawn because of “increasing lifespans and time spent in retirement, declines in personal savings rates and reduced access to workplace pension plans.”

CARP also pointed out in a document released after the 2015 budget was announced that mandating minimum RRIF withdrawals can be particularly punitive in years in which there is a severe market correction, such as during the global financial crisis of 2008-09: “RRIF withdrawals are calculated based on the asset value in January, and most people would not withdraw until December, by which time share values had plunged by as much as 50% in 2008. Seniors then had to take out twice as many shares, thereby depleting their deferral room at an even faster pace, especially if they also needed to redeem additional shares to pay the taxes.”

That year, in response to the crisis-induced issue, the government gave RRIF accountholders a 25% relief on their mandatory RRIF withdrawal. However, the relief was for 2008 only.

Despite these arguments, George and Golombek suggest that the government may have good reason for keeping minimum RRIF withdrawal factors.

“If you eliminate the RRIF minimums, you have an indefinite period of tax deferral [until death], which reduces government revenue,” George says. “And the government will say that by providing an indefinite period of tax deferral, RRIFs are not being used for their intended purpose, which is to provide retirement income.”

Says Golombek: “The question is: ‘Can we find a balance between the government’s need to raise revenue and seniors’ concerns about running out of money in retirement?'”

Not all policy organizations are enthused by the reduction in RRIF withdrawal minimums. The Ottawa-based Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) regards the initiative as something that will appeal only to wealthier seniors, who are in the enviable position of not needing to make more than the mandated minimum withdrawals from their RRIF to cover expenses.

But for those Canadian retirees who have relatively modest amounts in their RRIF, or no RRIF at all, other policy moves could be of greater benefit, the CCPA argues. For example, it says, an expansion in the Canada Pension Plan program, raising the guaranteed income supplement amount, or even reversing the decision to move the age of eligibility for the old-age supplement to 67 from 65 would benefit less affluent seniors.

“Those [initiatives],” says David Macdonald, economist with the CCPA, “would represent a more substantial positive change for most seniors, as opposed to changes to RRIF [withdrawal] minimums.”

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.