As Canada’s investment firms tackle the implementation of a series of major regulatory reforms and face the prospect of further regulatory upheaval, the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) is taking most of the heat from the investment industry’s compliance officers (COs) and company executives.

Investment Executive‘s (IE) 2015 Regulators’ Report Card found that the overall evaluations of both the investment industry’s self-regulatory organizations (SROs) and the major provincial securities commissions haven’t changed much over the past year – with the exception of the OSC’s. The overall rating for the OSC – Canada’s biggest and, arguably, most important regulator – has dropped notably this year amid heightened concerns about its lack of responsiveness and sensitivity to industry issues.

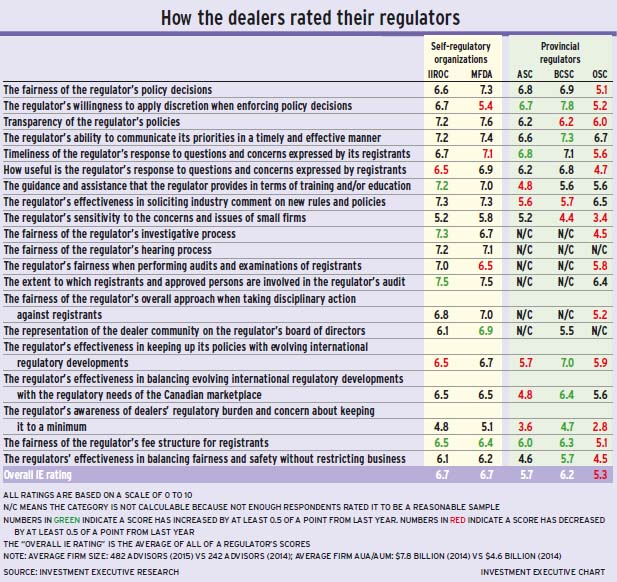

In fact, the OSC’s overall rating, at 5.3, is down significantly from 6.1 in 2014. Furthermore, its ratings are down year-over-year in almost every category IE asks COs and company executives to rate the regulators. As a result, the OSC now trails the other major provincial securities commissions – the Alberta Securities Commission (ASC) and the B.C. Securities Commission (BCSC) – in this year’s Report Card.

A notable caveat is that some survey participants were so negative regarding the OSC this year that they insisted on giving it ratings of zero in certain categories. Excluding these responses didn’t change the regulator’s overall score that much, but doing so did have a significant impact in a handful of categories – tempering the decline in certain ratings and even swinging the rating in one category from a decline to a modest improvement.

That said, the overall conclusion is that the country’s largest regulator earned lower grades from the investment industry this year.

Not surprising, the SROs – the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC) and the Mutual Fund Dealers Association of Canada (MFDA) – both received better overall ratings than any of the Big 3 provincial securities commissions.

However, not getting higher ratings would be very surprising, as the argument for a regulatory framework that includes self-regulation is that an SRO is closer to the industry – and more knowledgeable about its business models and operations. Therefore, SROs are expected to be more efficient and effective when it comes to supervising their members. So, the investment industry rating the SROs higher than it does the provincial regulators stands to reason.

“The SROs ‘get it’ because they’re closer to dealers. The [Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA)] doesn’t. They’ve loaded so much [regulation] on,” says a CO with an Ontario-based dealer on both IIROC’s and the MFDA’s platforms.

Indeed, IIROC and the MFDA were tied in this year’s survey for the top overall ratings. And although there was little change year-over-year in the overall ratings for both the SROs, this masks some shifts in their ratings for specific categories.

For example, IIROC received notably higher ratings this year in the following categories: “the fairness of the regulator’s investigative process”; “the extent to which registrants and approved persons are involved in the regulator’s audit”; and “the guidance and assistance that the regulator provides in terms of training and/or education.”

But investment dealers’ COs and company executives rated IIROC significantly lower in “the regulator’s effectiveness in keeping up its policies with evolving international regulatory developments” and “how useful is the regulator’s response to questions and concerns expressed by registrants.”

As for the MFDA, although most of the year-over-year changes in its ratings are relatively modest, its ratings in “the fairness of the regulator’s fee structure for registrants” and “the representation of the dealer community on the regulator’s board of directors” categories rose by half a point or more.

In contrast, the MFDA saw its ratings fall by the same margin in “the regulator’s willingness to apply discretion when enforcing policy decisions”; “timeliness of the regulator’s response to questions and concerns expressed by its registrants”; and “the regulator’s fairness when performing audits and examinations of registrants.”

In general, the investment industry is glad to have the SROs to turn to instead of having to deal directly with the provincial securities commissions.

“Thank God for the SROs acting as a buffer between us and the CSA,” says a CO with an Ontario-based dealer operating on both IIROC’s and the MFDA’s platforms.

Although that’s one reason that the SROs received better ratings from the investment industry than the provincial regulators, remembering that this Report Card measures perceptions from only one faction in the market – the investment industry – is important. Yet, the provincial regulators are saddled with the more delicate task of balancing the multiple, often conflicting interests of the investment industry, investors, issuers, government policy-makers and the overall health of the capital markets.

Thus, higher scores in this survey aren’t necessarily a good thing for the regulators, as the scores reflect only the investment industry’s view on things. For example, a new rule designed to protect retail investors may well be the right move for the markets overall, even though the investment industry itself resents the compliance burden that the new rule creates for the firms.

So, although each of the ASC, BCSC and the OSC registered the lowest rating in a specific category in this year’s Report Card, it’s important to remember that these ratings from COs and company executives represent only one aspect of what often are multi-faceted issues.

This tension is particularly relevant at a time when the investment industry is in the midst of implementing one of the most significant sets of regulatory reforms in the modern era: the second phase of the client relationship model (CRM2). In particular, CRM2 doesn’t just create a set of notable, new disclosure obligations for the investment industry; rather, they aim to redress the balance of power between the investment industry players and ordinary investors by endowing retail clients with a much deeper understanding of how well their portfolios are performing and how much they are paying for products and services they receive.

To some in the investment industry, CRM2 represents a lean too far in the investors’ direction.

“The investor protection mandate can be used to cloak anything, even if it’s irrelevant – CRM2, for example,” suggests a CO with an investment dealer based in British Columbia.

The implementation of CRM2 began in earnest last year and is slated to continue over the next couple of years. That process hangs over this year’s Report Card, as does the fact that regulators also are in the midst of several other, possibly seismic reform efforts, including: initiatives to consider a ban on trailer fees and the imposition of a fiduciary duty upon the provision of financial advice; far-reaching new measures to manage systemic risk under a newly created co-operative national securities regulator; and an overhaul of exempt-market regulation.

For now, though, the investment industry’s primary preoccupation is with CRM2 – and consternation with these reforms apparently is causing some COs and company executives to downgrade their regulators as a result. In certain cases, the SROs’ ratings also are taking a hit, even though the SROs can argue that they are doing the provincial regulators’ bidding regarding this file.

“The big issue is policy around CRM2. And I’m rating both IIROC and the OSC significantly lower because of their lack of practical knowledge,” says a CO with an Ontario-based investment dealer. “I’m completely supportive of the principles behind the reforms, but the execution is lacking in understanding and practical knowledge.”

It appears the OSC is taking the bulk of the heat for this attitude. For example, there was a suggestion, particularly among smaller firms, that the OSC is chiefly to blame for the investment industry’s perception that the details of these measures have been finalized without adequate concern for their practical impact – or that CRM2 favours the big banks.

“[The regulators] have little regard for the immense expense,” says a CO with an Ontario-based dealer operating on both IIROC’s and the MFDA’s platforms regarding the cost of implementing changes related to CRM2. “No accounting system in the world can do mid-month reporting, but they stuck it in anyway. We had to go on bended knee to the OSC to ask for a Dec. 31 reporting date instead of July 15.”

That same CO also added that certain issues are being resolved in favour of the large, bank-owned firms: “There’s no concern for boutiques. [Regulators] only care about the banks. For example, with money-weighted vs time-weighted rates of return, [the OSC] took what the banks are doing and applied it as the standard.”

This is a gripe about the OSC among some firms in general – and not just about CRM2.

“The OSC acts for banks and big players; it reacts to their interests,” says a CO with a boutique investment-management firm based in Western Canada, who added that the banks will benefit at the expense of smaller firms if the regulators decide to intervene on the question of trailer fees.

(It’s important to note that although survey participants included COs and company executives with some large asset-management firms and several big dealers, none were with the banks or bank-affiliated dealers).

Although the OSC has attracted much of the heat from the investment industry, the overall ratings for the ASC and BCSC didn’t change much – although those regulators did fare better with COs and company executives. Indeed, the BCSC received the highest overall rating among the provincial regulators, at 6.2 – and it’s the only provincial securities commission to earn the highest rating in some categories.

In fact, the BCSC was rated higher than even the SROs in “the regulator’s willingness to apply discretion when enforcing policy decisions” and the regulator’s effectiveness in keeping up its policies with evolving international regulatory developments.

As with the SROs, this headline stability does mask a certain amount of volatility in specific categories. For example, the BCSC saw its rating in “the regulator’s sensitivity to the concerns and issues of small firms” decline notably from last year – along with more modest declines in other categories.

However, these drops were offset by significantly higher ratings for the BCSC’s willingness to apply discretion when enforcing its policies, its fee structure, “the regulators’ effectiveness in balancing fairness and safety without restricting business” and “the regulator’s awareness of dealers’ regulatory burden and concern about keeping it to a minimum.”

As for the ASC, although its overall rating remained at 5.7 year-over-year, its ratings declined by half a point or more in five categories, including: keeping up its policies with evolving international regulatory developments, “the regulator’s effectiveness in balancing evolving international regulatory developments with the regulatory needs of the Canadian marketplace,” and for its awareness of dealers’ regulatory burden and concern about keeping it to a minimum.

In contrast, the ASC’s ratings rose significantly for its willingness to apply discretion when enforcing policy decisions, its fee structure and the timeliness of its responses to industry questions.

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.