Given the chance, there’s plenty the investment industry would change about its regulators. But the industry appears to be happier this year with the major watchdogs, according to Investment Executive‘s (IE) latest survey of senior industry compliance personnel.

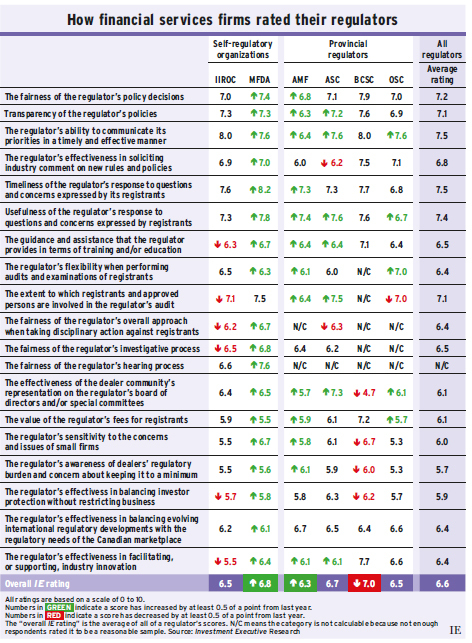

In the 2019 edition of IE‘s Regulators’ Report Card, the Mutual Fund Dealers Association of Canada (MFDA) and Quebec’s Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) made substantial gains. The other regulators that gained in our survey saw modest moves. The IE ratings for the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) and the Alberta Securities Commission (ASC) ticked up slightly this year, while the IE ratings for the B.C. Securities Commission (BCSC) and the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC) both declined. (An IE rating is the average of all the regulator’s category ratings.)

The regulators’ IE ratings now fall into a relatively narrow band – ranging from a low of 6.3 for the AMF to a high of 7.0 for the BCSC. Last year, the range was wider, with the AMF again on the low end at 5.3, and the BCSC at the high end with 7.5.

This convergence in overall IE ratings, and the underlying net increase in regulators’ scores, suggests the industry’s opinion was a bit higher this year than it was last year.

Higher approval ratings from the industry don’t necessarily mean regulators are doing a better job. The investment industry is just one among several constituencies the regulators serve – along with investors, issuers, politicians and the public. A good score from one faction is not a comprehensive evaluation.

Nevertheless, the surveyed compliance officers (COs) and executives are an important audience for the regulators.

The AMF gained one full point on its IE rating in this year’s Report Card; the MFDA wasn’t far behind, gaining 0.9 points. These substantial increases were driven by the strength of higher ratings in several areas. For instance, the MFDA received higher marks in 18 of the 19 categories that we asked industry compliance personnel to rate.

The AMF received higher scores in 15 out of 17 categories (we could not calculate marks for two categories due to an insufficient number of responses).

Ratings for the smaller provincial regulators (Alberta, B.C. and Quebec) are based on relatively small, but still meaningful, sample sizes, which means ratings can be volatile from year to year.

This year, the IE rating for the OSC – the biggest provincial regulator – rose a bit from last year. Its ratings were relatively stable year over year in most categories, such as “fairness of the regulator’s policy decisions” and “awareness of dealers’ regulatory burden.”

The OSC saw an increase in the effectiveness of dealer representation on its board and special committees. That category’s rating jumped by more than a full point from last year’s survey. The OSC’s marks declined in only two out of 16 calculable categories, and modestly.

IIROC’s IE rating dropped a little this year, as it saw lower marks in 13 out of 19 categories, with six of those drops being greater than half a point. The most notable drop came in IIROC’s rating for “balancing investor protection without restricting business,” which fell from 6.6 in 2018 to 5.7 this year.

On that front, comments indicated that IIROC is leaning too heavily in favour of investor protection. Several respondents said the organization should address significant issues, such as genuine conflicts of interest, but without adding paperwork to routine client interactions.

“Things are too paternalistic. They’re interfering in commercial matters,” says the CO for one of the big, bank-owned investment dealers. “They should focus more on conflicts, like compensation conflicts, rather than fees or product selection.”

These comments were echoed by several respondents. However, others said IIROC should prioritize investor protection.

“It’s not their job to facilitate business, it’s their job to protect investors and the public,” says the CO with a large firm. “It’s not their job to find the right balance.”

That said, a number of respondents stressed that IIROC needs more industry expertise, particularly on the examination side-a perennial industry complaint. “If they could recruit more people from the industry they’d get a broader perspective,” says a CO from an Ontario investment dealer.

Smaller firms said IIROC needs to do a better job of understanding their needs. At the same time, they said, it should be more skeptical of the inherent conflicts that exist in large integrated firms that house product manufacturing, distribution and advice.

Many of these themes applied to other regulators. Demands for more industry expertise and better training for the regulators themselves are things we heard in relation to the various provincial regulators.

Compliance executives also called for more flexibility from regulators in general, both in terms of the auditing process and in their approach to policy overall. A number of COs said regulators need to take a less prescriptive, more principles-based approach to oversight.

With regulators appearing to shift gears, the industry may yet get its wish. Instead of focusing on long-standing investor protection issues, such as raising conduct standards and reforming fund fee structures, regulators have recently turned to alleviating compliance burdens.

Time will reveal whether these efforts bear fruit. Meanwhile, compliance executives seem to like what they’re seeing.