Trading venture stocks in Canada is no fun these days. Global commodities prices and structural forces in the brokerage business appear to be conspiring against this segment of the stock market. Unfortunately, there’s no quick fix in sight, either.

Most segments of Canada’s capital markets have recovered nicely since the global financial crisis of 2007-09, but that’s not the case for venture stocks, for which trading – in terms of both volume and value – is at levels not seen since the global financial system was on the brink of collapse.

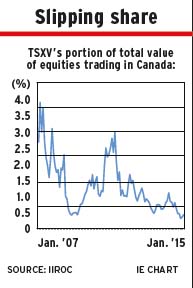

In fact, the TSX Venture Exchange‘s (TSXV) share of the value of total trading in Canada dipped to just 0.31% in late 2014, according to data from the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC). These trading metrics have recovered a tiny bit since, but remain well below the almost 4% share that the TSXV held in early 2007.

“The Canadian venture marketplace, the most dynamic and envied small-cap marketplace in the developed world, [is exhibiting] serious vulnerabilities,” warns Ian Russell, president and CEO of the Investment Industry Association of Canada (IIAC) in his latest newsletter to the investment industry, published in mid-March.

The apparent collapse of venture-stock trading is attributable to a variety of factors – from global macroeconomic influences, such as weaker commodities prices, to homegrown structural circumstances, including the ongoing deterioration at the boutique end of the brokerage business spectrum.

At the top of that list of factors, though, is commodities prices, which have been notably weak for the past several years – even before oil prices fell off a cliff. Many of Canada’s venture issuers are resources-sector companies, and it’s these junior firms that tend to suffer most when commodities prices plunge because junior firms don’t have the size or the business diversity to weather these storms.

Beyond commodities prices, the public markets for junior companies also face an assortment of other significant headwinds. For one, there’s the rise of the exempt market in Canada; increasingly, firms are bypassing the public markets because it’s more economical to raise funds in the less regulated exempt market.

Dealers and issuers alike have long complained about the regulatory cost of functioning as a public company in Canada. As a result, firms increasingly are forgoing the public markets and raising money in the private markets instead. Ordinarily, this choice would come at a cost of lower liquidity for investors, but, with venture-market trading activity disappearing, the liquidity advantage that the public markets once offered is evaporating. So, that’s one less reason for small firms to utilize the public markets.

One result of this shift away from the public markets and toward the private markets is the increasing dominance of large deals in the investment banking business, the IIAC notes. It reports that initial public offerings (IPOs) by small businesses “have been virtually non-existent” for the past two years; and small equity issues worth less than $20 million have fallen to a fraction of what they were before the financial crisis.

The dearth of smaller deals also spells trouble for the boutique investment dealers that focus on the small-cap market. These firms face greater competition for the few small deals that still exist; and with the decline in trading, boutiques lack alternative revenue streams to keep the business going in the absence of strong financing conditions.

For example, Russell says, market-making no longer is a profitable business for boutique firms, as trading spreads have been compressed and the costs of market data and connecting to multiple trading venues have risen.

As a result, the boutique end of the venture market is facing increasing consolidation. Firms are merging, decamping for the exempt market or closing shop altogether, Russell notes. Toronto-based Mackie Research Capital Corp.‘s acquisition of Vancouver-based Jordan Capital Markets Inc. in mid-February is just the most recent example of this trend. As Russell notes: “There’s a lot of these small, boutique firms that are being caught in the jaws of these various factors.”

There are demand considerations at play, too. Given that much of the investor base for venture stocks typically is retail, the participation of ordinary investors is critical to this part of the market. Yet, the IIAC notes, as the investor population ages in lockstep with the Canadian population, there may be a natural drift away from speculative, high-risk venture stocks and toward asset classes and investments that are perceived to be safer and less volatile.

Retail investors who are interested in riskier, more speculative companies, now are forced to follow the investment firms increasingly into the exempt market, in which investors may receive less stringent protection and no liquidity. Or investors may be excluded from these markets altogether by rules that are meant to limit participation to wealthier, so-called “accredited” investors.

“[These trends] are a shame because they foreshadow the continued erosion of the venture markets in Canada at a time when everyone else is trying to build them,” Russell says.

Indeed, the challenge of fostering vibrant venture markets isn’t an issue facing just the Canadian market. Although the resources-heavy TSXV is being hit particularly hard, the goal of creating a healthy environment for funding small, growing companies is an increasingly important concern for policy-makers elsewhere. That’s because small, fast-growing companies are highly valued as a strong source of job creation and economic growth at a time when both of those economic metrics remain persistently weak in many advanced economies.

To that end, the securities sub-committee of the U.S. Senate Banking Committee recently held a public hearing on the possible need for venture exchanges that are more tailored to the needs of small companies in the U.S.

The idea of a dedicated U.S. venture exchange is being touted as a possible answer to declining U.S. small-cap activity in recent years. U.S. securities regulators also are exploring other ideas, such as widening quoting and trading increments for small companies, as a way to boost market quality for small-caps.

A recent paper from New York-based IssuWorks Inc. and its investment-banking arm, Weild & Co., argues that much of the U.S. small-cap market’s troubles can be traced to changes in market structure that have taken place over the years. The paper argues that various trends – including exchange demutualization, the move to quote stocks in decimals and the inexorable drive toward low-cost trading – have helped to skew U.S. equities markets toward large-cap stocks at the expense of small-caps.

The paper also suggests that the evolution to for-profit, publicly traded exchanges has put exchange shareholders’ demand for profit ahead of the interests of dealers, small issuers and the trading environment for small-caps. To reverse that trend, the paper calls for a revival of the member-owned exchange model, among other things.

Whether there’s an interest in this suggestion within the U.S. is not yet known. However, Russell says, he’s skeptical that Canada could support the revival of the member-owned exchange model to combat the same forces here and to revive venture investing. Although, he writes, there is much to admire about the old mutual ownership model, “the genie is out of the bottle, and I don’t know how you go back.”

Given that many small-cap dealers are struggling to survive, there’s just not enough capacity in the Canadian market to support that effort, Russell suggests. Instead, he believes, the only real hope for stimulating activity in the venture markets is going to have to come from policy-makers in the form of tax and regulatory reforms.

For example, the IIAC advocates the creation of a new capital gains tax rollover provision, which would allow investors to defer their capital gains taxes if reinvesting their profits in qualifying small companies. The IIAC argues that this incentive could unlock capital that currently is tied up in low-return investments and redirect that capital to potentially more productive uses.

On the regulatory front, the IIAC is calling on the provincial securities commissions to require the retail distribution of exempt-market products to go through IIROC-licensed investment dealers. This change would drive more business to the suffering small dealers while also raising retail investor protection in the exempt market, Russell suggests.

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.