Fines don’t have much meaning when they don’t get collected. But securities regulators, particularly the self-regulatory organizations (SROs), have struggled to collect the fines and other monetary sanctions the regulators have imposed on investment industry players who go offside.

That’s because courts in most provinces don’t have the power to enforce these sanctions.

As a result, SROs such as the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC), are trying to increase pressure on provincial legislatures to pass legislation granting the regulators access to the courts. But the SROs are having a hard time persuading governments to make that happen.

In general, what’s required are greater enforcement powers under provincial securities legislation. Although many provinces agree these powers are necessary, changing the laws remains a low priority for most provinces. However, in the past year, IIROC has become increasingly vocal about the problem, renewing its call on legislators in many provinces to give the SRO the teeth it needs.

In making the request, IIROC can point to at least one recent success story. In late September, the Supreme Court of P.E.I. granted IIROC an order to enforce a settlement agreement with a former broker, who agreed to pay a $115,000 fine and $20,000 in costs. An IIROC hearing panel had found that he violated IIROC rules by making unsuitable recommendations to clients and trading without authorization.

Although the amounts are small, and P.E.I. is not a big player in the Canadian securities industry, the case highlights IIROC’s renewed efforts to collect the sanctions that it levies and to use the courts to make that happen.

Another problem for IIROC is that, once an advisor leaves the industry, the SRO has no authority over that advisor. So, for the sanctioned individuals, there’s no incentive to pay a regulatory fine if they are no longer in the business. And, in any case, they may not be able to pay; this is particularly so if they are also facing civil action as a result of the misconduct.

Whatever the reasons, IIROC’s collection rate for sanctions against individuals is weak. In IIROC’s most recent fiscal year (ended March 31), its hearing panels handed out approximately $2.4 million in monetary sanctions to individual advisors; of that total, the SRO collected just 16%, or $373,680. The situation regarding fined organizations is different: IIROC recovered 87% of the $1.55 million in penalties that were assessed against firms during the fiscal year.

While the success rate for collecting individuals’ fines may seem low, it has improved vs the previous year, when IIROC collected only 13.3% of its fines against individuals. Nor is inability to collect penalties just an IIROC problem; provincial securities commissions also struggle in collecting penalties against individuals.

From the regulators’ perspective, this fundamental inability to collect the vast majority of the financial sanctions the regulators order weakens their authority and undermines the deterrent effect that the threat of monetary penalties should have in preventing misconduct.

Until the P.E.I. case mentioned above came to light, the only provinces in which IIROC has been able to use the courts to try to enforce its disciplinary orders are Alberta and Quebec.

But IIROC is starting to make more noise. In February, it made a presentation to the Ontario government’s Standing Committee on Finance and Economic Affairs as part of that government’s pre-budget consultations, in which IIROC asked for the ability to enforce its hearing panel sanctions through the Ontario Superior Court of Justice.

“Such an enforcement tool would send a strong and credible message of deterrence and would advance IIROC’s public interest mandate [and] would foster investor confidence in the regulatory system – and it would do so at no material cost to government or taxpayers,” says Andrew Kriegler, IIROC’s president and CEO.

Yet, when Ontario’s provincial budget was tabled, new collection powers for IIROC did not make the cut. This is nothing new. In fact, IIROC’s predecessor, the Investment Dealers Association of Canada sought the same authority to enforce collections through the courts almost 15 years ago. For whatever reason, most provincial governments are reluctant to pursue the reforms necessary to give IIROC this power.

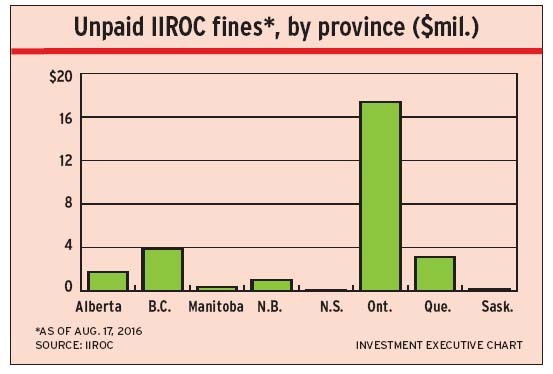

In the meantime, the tally of unpaid regulatory fines grows. Ontario is by far the most significant province in terms of uncollected sanctions, at almost $18 million, according to IIROC’s latest report. British Columbia is a distant second at slightly less than $4 million. And, despite having the ability to use the courts in Alberta and Quebec, there still are several million dollars in uncollected fines in those provinces.

Still, IIROC’s collection rates in Alberta and Quebec are much higher than they are in the rest of the country. For example, in Ontario, IIROC currently collects about 12% of the fines it levies against individuals. In Alberta, that rate is about 31%; in Quebec, 36%.

And, even if the governments in the other provinces do grant IIROC’s request and give it more power to collect monetary sanctions, the SRO still probably will not be collecting all of the amounts levied by its hearing panels.

Nevertheless, IIROC continues to try to bring more credibility to its enforcement efforts by lobbying for greater collection powers. The idea has backing from Canada’s largest provincial regulator, the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC). In mid-September, Maureen Jensen, chairwoman and CEO of the OSC, expressed her support of IIROC: “Strengthened enforcement against wrongdoers is clearly in the public interest.”

Kriegler suggests that the Ontario government does agree with the SRO about the need to step up its enforcement capabilities: “It is not a question of convincing governments that our view is right and another is not. There is no other view. The only task is to convince governments, here in Ontario and across the country, that the time to act is now.”

© 2016 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.