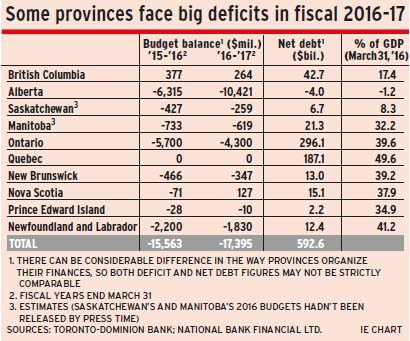

This year’s provincial budgets, on the surface, tell a twofold story. On one hand, the oil-producing provinces have big deficits, while finances in other provinces appear to be improving. However, serious budget challenges remain for most provinces.

Ironically, oil-dependent Alberta is the province with the greatest fiscal flexibility. Alberta’s budget forecast a deficit of $10.4 billion for fiscal 2017, ending on March 31 of that calendar year. And with the aftermath of the Fort McMurray fires, the deficit is likely to be higher. But years of good times mean that the province remained in a net asset position as of March 31, 2016.

And even with another three years of big deficits, Alberta is likely to survive the downturn in oil prices: at the end of fiscal 2019, the province’s projected net debt of $33.2 billion will be only 8.9% of provincial gross domestic product (GDP), a very low percentage compared with that in other provinces.

Newfoundland and Labrador is in the worst shape. Even after raising almost every tax and user fee, plus introducing a special “deficit reduction levy,” the province is expecting a deficit this fiscal year of $1.8 billion, not much lower than fiscal 2016’s $2.2 billion. Perhaps even more sobering, the province is now projecting deficits through fiscal 2023. That would mean a debt burden in that year of around $16.5 billion – 50% of GDP.

New Brunswick also is struggling. Although it is benefiting from both low oil prices and the low Canadian dollar (C$), the province doesn’t expect to balance its books until fiscal 2021. New Brunswick’s biggest problem is negative population growth, as residents leave in large numbers for better job opportunities. Indeed, the budget assumes economic growth of 0.5% in 2016-18.

One challenge for all of the provinces, says Mary Webb, director of economic and fiscal policy for Bank of Nova Scotia in Toronto, is to have agreements with Ottawa that qualify the provinces for as much federal money as possible – not just for infrastructure, but also for special programs, such as support for First Nations peoples.

Here’s a look at the provinces’ budgets in more detail:

– British Columbia. B.C., the brightest spot in Canada, anticipates that budget surpluses will continue. The province is benefiting from the low C$, which enhances profits on exports. Those includes lumber sales to the recovering U.S. housing industry. The caveat is that renegotiation of the Canada-U.S. Softwood Lumber Agreement, which will happen after the November U.S. presidential election, could reduce the U.S.’s lumber imports from Canada.

Longer term, there’s the prospect of liquified natural gas plants and exports, but this industry is heavily dependent on new pipelines, a political issue fraught with controversy in both Canada and the U.S.

B.C. is also benefiting from its popularity with other Canadians: migration from other provinces is pushing B.C.’s population higher and helping to fuel economic growth. The downside for homebuyers is an extremely hot housing market that is pricing many consumers out of the market. To ease this problem, a five-year “affordability” program has been announced, as well as more relief from property transfer taxes for Canadian citizens.

The B.C. budget also established a Prosperity Fund, with initial funding of $100 million. This fund aims to pay down the provincial debt, enhance health care and education services, and put money aside for future generations.

– Alberta. The New Democratic Party (NDP), after winning the May 2015 election, replaced the flat 10% personal income tax rate with a progressive tax system, brought in a new child benefit, increased the corporate tax rate, increased the minimum wage and announced a carbon tax.

The few new measures in the 2017 budget were aimed at offsetting the negative impact of the carbon tax on lower-income individuals (who will receive rebates) and small businesses.

– Saskatchewan. The governing Saskatchewan Party, which won the April 4 election, will bring down its budget on June 1. In late February, the government forecast a $259-million deficit for fiscal 2017. Election promises included no tax increases and no cuts to health care, education and social services.

– Manitoba. The NDP government was defeated in the April 19 election by the Conservatives. No budget date has been announced, but Montreal-based National Bank Financial Ltd. estimated in early March that the province was heading toward a $619-million deficit for fiscal 2017. Election promises include lowering the provincial portion of the harmonized sales tax (HST) to 7% from 8% by 2020.

Last December, the previous NDP government had committed to a “cap and trade” system to lower greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions. So far, however, the new government has not addressed this issue. The cap-and-trade system puts a ceiling on total GHG emissions in the province. Under such a system, businesses needing to emit more GHG than is allowed must purchase permits from firms not using their full emissions allowance.

– Ontario. The province didn’t need major personal or business tax increases to remain on track to balance its budget in fiscal 2018. The main focus of Ontario’s budget is initiatives that were announced previously: a cap-and-trade regime for GHG, ongoing investments in infrastructure and the Ontario Retirement Pension Plan (ORPP). However, the ORPP will go ahead only if federal/provincial negotiations don’t result in enhancements to the Canada Pension Plan.

– Quebec. The province is unofficially in surplus and expects to remain so. Officially, Quebec records a zero deficit each year because it puts extra revenue in the Generations Fund; its mandate is to help to reduce the debt.

The budget didn’t raise major taxes, but did introduce a tax credit for qualified green housing renovations. As well, the personal health contribution is being phased out.

– New Brunswick. The province was forced to raise its portion of the HST to 10% from 8% as of July 1. New Brunswick also increased its corporate and its manufacturing/processing tax rates to 14% from 12%; its financial capital tax to 5% from 4%; and the real property transfer tax increased to 1% from 0.5%, all as of April 1 this year. However, the province eliminated its top tax bracket and lowered the rate for taxable income above $150,000 to 20.3% from 21%, as of Jan. 1, 2016.

– Nova Scotia. Despite declines in this province’s offshore gas royalty revenue and no major tax increases, Nova Scotia is forecasting surpluses for this year and the next three years. Population growth is barely positive, but real GDP is expected to grow by about 1% a year in 2016 and 2017.

– Prince Edward Island. Although P.E.I.’s tourism industry is benefiting from a lower C$, the province missed its balanced budget target for fiscal 2016 and is raising its portion of the HST to 10% from 9% as of Oct. 1, 2016, to produce a surplus of $9.2 million in fiscal 2018. On the plus side, P.E.I. is removing the land transfer tax for first-time homebuyers.

– Newfoundland and Labrador. The province raised almost all taxes and fees. The province’s new corporate tax rate of 15% is higher than New Brunswick’s 14% but below Nova Scotia’s and PEI’s 16%. The unchanged small-business tax rate of 3% is the same as Nova Scotia’s and less than New Brunswick’s 3.5% and P.E.I.’s 4.5%. The province’s top combined federal/provincial marginal tax rate is 49.8%, which is lower than in all other provinces east of Saskatchewan.

© 2016 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.