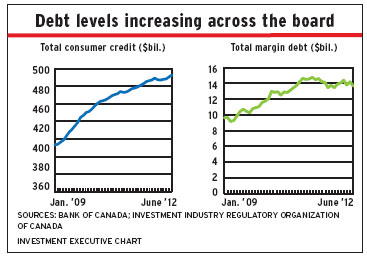

It seems that each passing day brings further evidence that Canadian households are loading up on excessive debt – mostly in the form of mortgage debt and consumer credit. What doesn’t seem to be well understood is the extent of investment debt, and the risk that it could pose to a household’s financial health.

For several years now, the Bank of Canada (BoC) has been warning about the accumulation of household debt, which is widely acknowledged as the biggest homegrown vulnerability in the Canadian economy. As debt burdens inflate, the fear is that households become increasingly susceptible to economic shocks, such as a significant rise in unemployment or a big jump in interest rates, which could mean indebted households would not be able to afford to continue servicing their debts.

Those fears were further stoked in mid-October, when Statistics Canada announced that household credit-market debt now has reached 163.4% of disposable income (as of the end of the second quarter of 2012). The level is a bit shocking because it is much higher than previously thought and seems to be entering some dangerous territory.

The 160% mark, according to Toronto-based Royal Bank of Canada‘s economics department, “happens to be the level at which both the U.S. and Britain experienced a sharp deterioration in household credit quality that spurred on the collapse of their respective housing markets and helped trigger the recent global economic downturn.”

Although worries about Canadians’ household debt position have been building for some time, until now, the debt/income ratio was thought to be closer to 150%. However, changes to economic accounting practices that are now just being adopted have resulted in revisions that put the ratio notably higher and indicate that it has been growing faster than previously thought.

Moreover, the revised figure highlights the extent to which Canadians have become willing to use debt to fund their lifestyles, despite policy-makers’ efforts to curb this practice.

So, if there’s an overall household debt bomb lurking on our nation’s balance sheet, could there also be a similar risk facing investors’ portfolios?

The Canadian Foundation for the Advancement of Investor Rights (a.k.a. FAIR Canada) sounded the alarm on this issue a year ago. In a letter sent to securities regulators in October 2011, the investor advocacy group flagged leveraged investing as a systemic problem.

And in a more recent submission to the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC), FAIR Canada suggests leveraged investing is particularly inappropriate in the current market environment: “In these volatile times, the leveraged purchase, particularly of high-fee products, is simply a meritless strategy that will result in significant financial losses to the majority of consumers.”

What’s not clear is just how significant the problem could turn out to be. It seems that no one, including the investment industry’s regulators, has good data on the full extent of leverage in the system.

According to statistics published by IIROC, monthly margin debt levels in its member firms’ client accounts have generally been on the rise since the start of 2009 – although not to unprecedented levels (and they had declined to $12.8 billion as of the end of August).

The Mutual Fund Dealers Association of Canada (MFDA) estimates that about 3% of overall assets under administration, which includes other securities as well as mutual funds, on its member firms’ books are in accounts utilizing leverage. Approximately one-third of this involves borrowing to fund RRSP and registered education savings plan account contributions, says Karen McGuinness, the MFDA’s vice president of compliance. The regulator, she adds, is not particularly worried about this sort of leverage.

The MFDA is more concerned about borrowing to fund investments in non-registered accounts. About 110,000 non-registered accounts at mutual fund dealers utilize leverage, representing about $8 billion in leveraged investments.

However, those numbers don’t give a complete picture of the risk posed by investment leverage. The $8 billion in non-registered accounts at MFDA firms is measured at market value, and it’s impossible for the regulator and, in many cases, the dealers to know the extent to which clients might be underwater on these loans.

In order to assess whether these leveraging strategies are proving profitable or not, the MFDA would need information from lenders on outstanding loan balances, interest payments and distributions, McGuinness explains. Furthermore, the dealers would need co-operation from lenders, which is not always forthcoming, along with client consent, to collect that information.

Moreover, McGuinness points out that clients could be drawing on a line of credit to fund an investment rather than a discrete investment loan. So, it is tough for either the investment firms or the regulators to get a true picture of the full extent of this sort of borrowing.

Indeed, earlier this year, IIROC issued new draft guidance on the suitability of leveraged investments calling on dealers to ensure that they properly supervise both “on-book” leverage strategies, in which the financing is arranged through the dealer, and “off-book” leveraging, in which the funding comes from an external source. In some cases, off-book leveraging is arranged by the dealer rep; in others, a client could be investing with borrowed money and this fact may not even be disclosed to the dealer by the client.

IIROC’s proposed guidance aims to ensure this sort of off-book borrowing comes under some supervision. The guidance paper says that whether a financial advisor is recommending a leverage strategy or learns of the client’s plan to use leverage, both the firm and the rep have an obligation to ensure suitability and to make certain that the rest of IIROC’s rules are followed.

Although IIROC’s guidance paper acknowledges that undisclosed, off-book borrowing by a client can be very difficult to detect and supervise, the paper insists that dealers and reps watch for this sort of borrowing. The guidance paper sets out best practices for dealing with such a scenario.

However, judging by some of the comments in response to IIROC’s draft guidance, the dealers don’t want this responsibility. The Investment Industry Association of Canada‘s (IIAC’s) comment on the proposed guidance argues that not only will ferreting out the existence of all leveraged loans require costly systems changes, it will still be very hard to comply even if new systems are developed.

According to the IIAC comment: “There is no reasonable way for members to effectively supervise “off-book” accounts, which are especially problematic to both detect at the onset and monitor on an ongoing basis.”

The IIAC comment adds that the proposed guidelines are too prescriptive and too far-reaching.

The reality is that it’s very difficult for either the firms or the regulators to keep track of this sort of leverage in the system. And there doesn’t seem to be good information available from the lending side, either.

The federal banking regulator, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, says it doesn’t have specific data on investment borrowing. Neither does the BoC, the Canadian Bankers Association, Statistics Canada or the Ontario Securities Commission.

But it’s not just the existence of off-book leverage that has regulators concerned; it’s also the wisdom of leveraged strategies in general. IIROC, in its proposed new guidance, notes that its compliance exams have turned up “an increasing number of cases in which inappropriate leveraging strategies have been recommended to clients”; and, that it has also found cases of insufficient disclosure to clients of the debt-servicing costs, and the risks, of using leverage to invest.

FAIR Canada’s letter to the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) a year ago warns that leverage is not suitable for most retail clients; and further argues that leverage should be presumed to be unsuitable – placing the onus on the dealer and the rep to prove suitability before an investment can be made. FAIR Canada has reiterated these concerns in its submission on IIROC’s latest guidance, while indicating that there hasn’t been any meaningful response to its original letter.

FAIR Canada’s comment calls IIROC’s proposed guidance “a laudable initiative” but doubts that it will do much to improve investor protection: “In the absence of further action by the CSA, IIROC and the MFDA, the proposed leverage guidelines will not be sufficient to prevent more consumers from being put into high-risk leveraged situations to which they are not suited.”

Unfortunately, it’s impossible to gauge just how significant that risk is, given the lack of data on the true extent of leverage in the Canadian investment market.

A so-called compliance “sweep” carried out by the New Brunswick Securities Commission (NBSC) in 2010 that focused on leverage at both IIROC and MFDA firms found that while leverage was generally being used appropriately among the firms being reviewed, investors were suffering losses and in unsuitable investments.

In particular, the NBSC report found that 36% of the accounts it reviewed were in a loss position; 9.6% were invested in unsuitable investments; and, 23.7% were considered aggressive and possibly unsuitable.

It’s not clear that these findings can be extrapolated to the rest of the country. But if Canadian consumers’ borrowing habits are any sort of reliable guide, the problem could prove to be a big one.

© 2012 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.