Global fixed-income markets were fruitful last year, as bond yields stayed low or, in some cases, fell lower, producing capital gains for investors. But 2015 already is proving to be challenging, with uncertainty about the impact of declining inflation, which is due, in part, to dramatically weaker crude oil prices. Mutual fund portfolio managers are treading carefully, mindful of the fixed-income and currency challenges ahead.

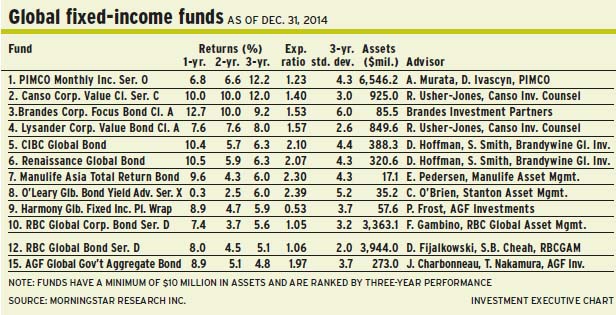

“There’s an abundance of riches, in terms of reasons why yields are falling, and all of them are leading in the same direction,” says Dagmara Fijalkowski, senior vice president and head of global fixed-income with Toronto-based RBC Global Asset Management Inc. and portfolio co-manager of RBC Global Bond Fund. She shares portfolio- management duties with Soo Boo Cheah, portfolio manager with London-based RBC Global Asset Management (U.K.) Ltd.

“Compared with a year ago, there are some additional fresh reasons, including falling inflation expectations, which are tied to falling oil prices,” adds Fijalkowski. As evidence, she points to the break-even yields on 30-year U.S. Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS), which have fallen to 1.8% from 2.4% since last July.

“You have to believe that over 30 years, inflation will exceed 1.8% to believe TIPS are a good buy,” says Fijalkowski, adding that 10-year TIPS yields also have fallen by 70 basis points (bps) in the same period. “All of this is clearly related to the oil prices we’ve seen.”

The steep decline in oil prices is significant because it could be a harbinger of other “dominoes to fall,” says Fijalkowski. “There may be consequences that we are not even aware of. People are thinking about the impact on consumers and revenue of production companies. But there may be other unintended consequences that will contribute to volatility.”

Throw in the fact that the Swiss National Bank suddenly abandoned its Swiss franc/euro exchange rate peg in January, sending panic into currency and fixed-income markets, and no wonder frightened investors have bought government bonds. “That’s the other fresh reason for yields to keep falling,” Fijalkowski says.

Moreover, she notes, investors have flocked to 10-year U.S. treasuries, which yield 1.9% compared with 10-year German government bonds that yield 0.5% or with 10-year Japanese sovereign bonds that yield 0.25%.

Yet, on a valuation basis, U.S. treasuries are expensive, Cheah says: “They are expensive relative to growth and inflation expectations. But they could stay expensive for a bit longer.”

Cheah notes that the global bond market is dominated by so-called “price-insensitive” buyers who act on behalf of other central banks and super-large pension funds.

From a strategic viewpoint, Fijalkowski is cautious. The RBC fund has an average duration of 6.4 years, vs seven years for the benchmark Citigroup world government bond index (Canadian dollar [C$]-hedged). The RBC fund, which has more than 350 holdings, has a running yield of 2.4%, vs 1.9% for the benchmark.

From an asset-allocation basis, the bulk of the RBC fund’s portfolio is in sovereign bonds, with U.S. and Canada accounting for about 37% of assets under management (AUM); Europe, 38%; Japan, 16%; and about 9% in the riskier classes of emerging markets and high-yield bonds. The fund is 92% hedged back into C$, with the remainder split among several developed countries’ currencies.

The two drivers behind falling yields are weakness in global economic growth rates and continued bank deleveraging, argues Alfred Murata, managing director with Newport Beach, Calif.-based PIMCO LLC and portfolio co-manager of PIMCO Monthly Income Fund. He shares portfolio-management duties with Daniel Ivascyn, chief investment officer with PIMCO.

“Europe is an area where there is continued weak credit growth and negative growth in the private sector,” Murata says. “Japan is another area we are quite cautious on.”

There are many reasons to be worried, adds Murata. “There continues to be a large debt overhang in Europe, plus a large debt overhang and demographic challenges in Japan. And there are continued risks around China and its ability to achieve its long-term growth rates. We’re not sure if [those rates] are sustainable. If there is a slowdown, it’s bound to have an impact on commodity producers.”

Yet, Murata argues, most developed world government bonds are not attractive – with the exception of Australia, where rates may decline.

“Even if global growth stays at current levels for an extended period of time,” Murata says, “there does not seem to be much prospect of significant [bond price] appreciation.”

An analysis by PIMCO analysts that looks out five years takes the view that the market is pricing 2.39% into five-year bonds, which, Murata argues, does not leave much cushion in comparison to the 2% inflation rate.

“We are not being compensated for the risk of holding government treasuries,” says Murata, adding that he expects the U.S. Federal Reserve Board to raise interest rates around mid-year but the move will not have much impact outside the U.S.

The PIMCO fund’s prime objective is to generate income, says Murata, adding that the fund has a distribution yield of about 4%. But the fund also is focused on maintaining stability of its net asset value to protect the fund against the downside. Given the low interest rate environment, the PIMCO fund has an average duration of three years vs five years for the benchmark Barclays U.S. aggregate index (C$-hedged).

On a geographical basis, the U.S. is the largest country weighting, at about 53% of the PIMCO fund’s AUM, followed by the U.K. (7%), Brazil (6.9%) and smaller weightings in countries such as Ireland (3.8%).

The PIMCO fund has a bias toward higher-yielding assets, such as non-agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and high-yield bonds that will benefit from strong economic growth. On a duration-weighted basis, this portion of the fund accounts for about 70% of AUM. The balance, 30%, is held in higher-quality assets, such as Australian sovereign bonds and investment-grade corporate bonds that protect against weaker growth.

“It’s a see-saw approach,” says Murata, who uses a blend of top-down and bottom-up methodologies and is backed by a team of 200 portfolio managers and analysts who monitor the 500-plus holdings in the PIMCO fund.

Referring to the MBS market, Murata adds: “[MBSes] offer a combination of a decent yield in the base case, potential for upside in more optimistic scenarios and reasonable downside protection. In aggregate, we find this sector to be a lot more attractive than investing in corporate high-yield. In the base case, we expect U.S. home prices to increase by about 3% a year. That would correspond to a loss-adjusted yield of 5%-6%.”

If the housing market recovers at a faster pace, he adds, the loss-adjusted yield would be above 7%. “And even if house prices drop by 5% a year,” he adds, “we could still earn 2% on a loss-adjusted basis.”

Global bond market volatility is being driven by slumping global economic growth, says Jean Charbonneau, senior vice president with Toronto-based AGF Investments Inc., and co-manager of AGF Global Government Aggregate Bond Fund. He shares portfolio-management duties with Tom Nakamura, vice president of AGF.

“There is hardly any growth worldwide,” says Charbonneau. “Japan is about to reflate its economy. There is flat growth in the eurozone. China is struggling to get around 7% gross domestic product growth, which is not bad – but not great for China; I’m looking at 6% this year. And Brazil and Russia are almost in recession. The U.S. is growing – it’s the brightest picture, globally – but 2.5%-3%% is not enough. That’s why [interest] rates are so low.”

Additional factors contributing to low rates are disinflationary pressure in many parts of the world, combined with deflationary trends in Europe. Moreover, Charbonneau believes that even if the U.S. Fed is the sole exception among central banks and raises interest rates, it is likely to wait until the fourth quarter.

“I don’t see why the Fed should hike rates, given that wage growth has been lower than expected – and well within [the Fed’s] 2% annual target. There is no urgency to move soon,” says Charbonneau. “I’m in the camp of ‘later rather than sooner’.”

From a valuation standpoint, Charbonneau agrees that government bonds are expensive. “But when you put that into context with disinflationary pressures around the world and some deflationary pressures in other parts, bond markets are doing OK,” says Charbonneau, noting that the 1.9% yield from 10-year U.S. treasuries is within the range for the past 12 months.

However, he adds, the worries are not overdone. Central banks, such as the European Central Bank (which plans to unveil quantitative easing program this spring), are key players in global markets. Says Charbonneau: “Economies need to be supported by excess liquidity from central banks.”

Charbonneau anticipates a slight flattening of the yield curve in the U.S. this year. He describes himself as a “modestly aggressive” investor. The AGF fund’s average duration is 6.21 years, compared with 6.38 years for the benchmark Barclays Capital global aggregate bond index. The AGF fund holds 70 to 80 individual securities.

The U.S., representing 40% of the AGF fund’s AUM, is “a good place to be invested, given the strength of the [U.S.] dollar,” says Charbonneau, adding that the U.S. economy is rebounding, the Fed’s monetary policy is more advanced than that of other countries and yields are about 150 bps higher for U.S. treasuries than for comparable German government bonds.

Slightly more than half of the U.S. exposure in the AGF fund is in government bonds and 17% of AUM is in U.S. corporate bonds. Otherwise, from a country viewpoint, 30% of AUM is in the eurozone, 12% is in emerging markets, and there are smaller holdings in New Zealand, Australia and Japan.

From a currency perspective, 35% of the AGF fund is hedged back into the C$.

Charbonneau anticipates that after high single-digit returns in 2014, the AGF fund’s returns will be somewhat lower: “I’m looking at below 5% returns – unless we see a massive deflationary scenario,” he says, “which I don’t give a high probability. All in all, getting a 4% return is achievable.”

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.