If the recent turmoil in the financial markets has you losing sleep, it’s time to rest easy, according to global portfolio managers. Most of these portfolio managers believe the recent setback is a temporary correction in an equities bull market that still has legs. Stock valuations weren’t in bubble territory before the correction, they say, and now are at levels that present opportunities for savvy investors.

The roots of the turmoil lay in the alarm felt by investors over weak economic data, particularly in Europe and Japan, in what should be a strong growth environment, given the enormous monetary and fiscal stimulus programs instituted by the U.S. and other nations.

What sparked the sell-off in equities was a downward revision by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Oct. 7 to its forecast for global economic growth this year, revising the forecast to 3.3% from 3.7%. The alarm over that revision was exacerbated by some other potential negatives – such as the end of quantitative easing (QE) in the U.S., the rise of terrorism related to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in the Middle East, the Russia/Ukraine conflict and the Ebola virus epidemic – all of which investors previously had been taking in stride.

The result of the widespread alarm was a plunge in equities prices around the world. Most stock market indices, including the S&P/TSX composite index, bottomed on Oct. 15-16, dropping by 7%-12% in value. However, many indices gained back a good deal of this drop; at the close on Oct. 17, most stock markets were off by just 3.5%-4% from Oct. 6 – although Germany’s DAX index still was down by 6%. At press time, the jitters were continuing, with some markets up and others down.

Although most portfolio managers anticipate a rebound and the equities bull market to continue, they think there also will be a lot of volatility. In fact, they don’t think that’s a bad thing.

Before stock markets plunged, says Craig Basinger, chief investment officer (CIO) with Richardson GMP Ltd. in Toronto: “[Investors] didn’t seem to care about any bad news.”

Craig Alexander, senior vice president and chief economist with Toronto-Dominion Bank in Toronto, believes investors felt that as long as central banks were printing money, equities were a “one-way bet” that stocks would inevitably keep rising.

Suddenly, investors woke up to the fact that the U.S. Federal Reserve Board is ending its QE program at the end of November and no longer will be pushing liquidity into the financial system. Certainly, the imminent end of the Fed’s QE program was a contributing factor to the stock market drop, raising the possibility that the Fed soon will increase short-term interest rates. This would create inflationary expectations that push up long-term interest rates and could send the U.S. economy back into recession.

However, this highly unlikely, says Jurrien Timmer, director of global macro with FMR LLC (a.k.a. Fidelity Investments) in Boston. The Fed is “hypersensitive” to inflation expectations, he says, and will act quickly to squash them.

Nevertheless, there’s also a possibility that investors are starting to doubt the ability of central banks to fix the economy. After all, the Fed has been pumping money into the system for years and growth is still modest. Similarly, more recent efforts by the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan haven’t produced growth.

Wendell Perkins, senior portfolio manager with Manulife Asset Management (U.S.) LLC in Chicago, was surprised at how “vicious” this correction has been and is, in fact, worried that investors are doubting the ability of central banks to keep their economies growing. If that’s the case, the correction won’t be as short and shallow as expected.

However, most portfolio managers believe that investors will relax once they realize that 3.3% global growth isn’t that low, which will cause the equities bull market to resume. In the meantime, these portfolio managers picking up good stocks that have fallen to unreasonably low valuations.

Several portfolio managers, including François Bourdon, chief investment solutions officer with Fiera Capital Corp. in Montreal, and Charles Burbeck, co-head of global equity portfolios with UBS Global Asset Management (U.K.) Ltd. in London, are looking at international equities because their valuations weren’t as high as U.S. equities before the correction – and they’re now even lower.

“The consensus on Europe has become so negative that we expect those expectations to be beaten,” says Bourdon, adding that China and Japan will stimulate their economies and do better than expected.

Some portfolio managers believe that U.S. equities are the place to be, even with their higher valuations. Basinger, for example, is focused on retailing and hotel stocks. Even before the recent sell-off, their prospects were good because of the drop in consumer debt (which has fallen to 90% of disposable income from 114% in 2009), the drop in the unemployment rate and declining gasoline prices. Also, wages are rising.

Here’s a look at various factors affecting equities markets:

– Economic growth. Although global growth of 3.3% isn’t great, it isn’t alarmingly weak. In addition, the IMF expects the pace of growth to rise to 3.8% next year, which is close to the 3.9% annual average seen from 1996 to 2005.

The reasons for this: the U.S. economic recovery is well entrenched; most economists expect China’s economy to keep growing by about 7% a year; and the drop in Japan’s gross domestic product (GDP) in the second quarter of this year is considered a blip caused by an increase in its sales taxes to 8% from 5%. Furthermore, governments in both China and Japan are expected to do what it takes to make sure their economic growth continues.

Europe, however, is very worrisome. Germany’s government has revised its forecast for GDP growth this year downward to 1.2% from 1.8%, and to 1.3% from 2% for 2015. And if Germany falls into recession, so will pretty much every other country in Europe.

Further complicating the picture in Europe is that the results of the ECB’s bank stress tests will be released on Oct. 26. If the results are more negative than expected, that could pull Europe-based equities down further.

– Low inflation in Europe. Extremely low inflation numbers in Europe suggest that deflation could be around the corner. And once prices start dropping, consumers will put off purchases because they expect prices will drop further – and it’s very hard to get consumers spending again.

The only potential good news, Alexander says, is that with Germany’s GDP growth slowing, that country may agree to allow the ECB to pursue more aggressive monetary stimulus. This could include the purchase of assets to increase private-sector liquidity and kick-start the economy.

The problem, says Timmer, is that this may not work. European banks depend more on bank lending than the bond market, and European banks “aren’t in the mood to lend.”

– The U.S. dollar. The rise in the U.S. dollar (US$) is long overdue and is a relief for Europe. With domestic demand so weak in Europe, exports are a critical ingredient in generating economic growth – and a lower euro vs the US$ makes European goods more competitive.

The greenback is likely to continue strengthening for both fundamental and psychological reasons. The U.S. will be the first industrialized country to raise interest rates, which will produce an inflow of money that will increase demand for the US$. Interest rates are expected to start rising in late 2015 or early 2016, although that could begin in the middle of next year.

The US$ also is considered to be a safe haven in times of uncertainty – and the uncertainty about Europe, China and Japan is likely to last some time.

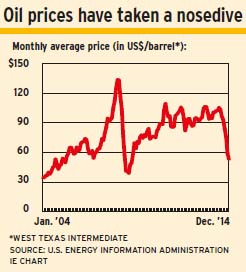

– Oil prices. The price of West Texas intermediate has dropped to around US$80 a barrel and could stay around that level because of ample supply. U.S. supplies from shale production are rising, and Saudi Arabia and other members of the Oil Petroleum Exporting Countries have no plans to cut their production. In addition, slower GDP growth in China and other emerging countries is keeping a lid on growth in demand.

A lower oil price is bad news for oil-producing countries such as Canada. But, for many other countries, a lower price is good news because lower gasoline prices give consumers more money to spend – certainly the case in the U.S., Japan, many European countries and some emerging markets.

In addition, notes Leo de Bever, CEO and CIO of Alberta Investment Management Corp. in Edmonton, lower oil prices will cut costs for many companies.

– Sanctions against Russia; Isis; and ebola. These are risks that can’t be forecasted because they don’t depend on economic fundamentals. However, these factors still pose a danger to global economic growth.

© 2014 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.