The natural resources sector has experienced a “Lazarus-like” recovery of late. Crude oil and gold bullion prices are up significantly, pushing many related stocks back into positive territory. Could it be that the worst of the lengthy bear market for resources is behind us?

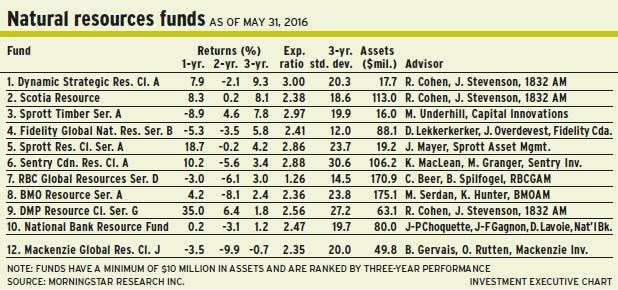

“There was a fear of bankruptcy, by and large, in both materials and energy stocks,” says Brahm Spilfogel, vice president at Toronto-based RBC Global Asset Management Inc., (RBCGAM) and portfolio co-manager of RBC Global Resources Fund. (He shares portfolio-management duties with Chris Beer, another RBCGAM vice president.) “The rebound in the past three months represents the lessening of those fears. It’s been a relief rally.”

Take, for example, Freeport-McMoRan Inc., a major copper producer that made an ill-timed acquisition of oil and gas player Plains Exploration Inc. in 2013. The market has looked positively on Freeport-McMoRan as it sold off assets to pay down debt at the same time as copper and iron ore prices rallied modestly.

“It doesn’t look as if pricing is going lower. There is a sense in the market that we have probably seen the bottom,” says Spilfogel.

Crude oil prices also have been moving upward as the North American oil and gas industry reduces output, Spilfogel says.

Is the price of crude oil – now approaching US$50 a barrel – sustainable? “We’ve gone from an oversupply situation to one that should be more balanced between now and the end of the year,” says Spilfogel, noting that global demand is expected to grow by about one million barrels a day.

“Some would argue that we are already balanced, if not undersupplied. That’s one reason the oil price has stopped going down.”

From a strategic viewpoint, Spilfogel and Beer have allocated about 57.8% of the RBC fund’s assets under management (AUM) to energy and 39.3% to metals and mining, plus about 3% to cash. On a geographical basis, about 52% of AUM is held in the U.S., 26% is in Canada, with smaller holdings in countries such as France and the U.K.

A top holding in the RBC fund’s portfolio of 65 names is Concho Resources Inc., an oil and gas player in Texas’ Permian Basin that produces about 120,000 barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) a day. “[Concho’s] balance sheet is good and [the company has] good management,” says Spilfogel.

Concho stock is trading at about US$120.25 ($151.20), or about 12.5 times enterprise value to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

The sudden rebound in resources is characteristic of a sector that tends to overdo it, in either direction, says Benoît Gervais, senior vice president of investments with Toronto-based Mackenzie Financial Corp. and lead portfolio manager of Mackenzie Global Resource Class Fund.

“As we say in our space: ‘You’re either a contrarian or a victim.’ These sectors are either greatly oversold or overbought. Seldom do we spend time in the reasonable middle,” says Gervais, who shares portfolio-management duties with Onno Rutten, vice president, investment management, with Mackenzie.

Gervais maintains that the lengthy commodities bear market reflected the fear that emerging markets [EMs] were written off.

“Despite very long-term demographic themes that said there was a growing middle class [in EMs], the [commodities] market believed there was little optimism to be had in those [EMs],” says Gervais. “People would ask, ‘Why would I need high-volatility exposure to something that’s not working? Too much debt, not enough growth. This is a bubble, get me out’.”

Gervais argues that resources markets began to turn around when they recognized slowing global growth was bound to impact the U.S. In fact, U.S. Federal Reserve Board officials began to admit that the U.S. was not insulated from developments elsewhere.

“There was also the recognition [in the markets] that if energy was to blow up, it would blow up the high-yield bond market – and would hurt some of the banks,” says Gervais. “The thinking became something like: ‘We can’t let the commodity world go to zero and still expect to do OK. There has to be some balance’.”

Briefly put, Gervais believes that natural resources stocks quickly went from extremely oversold to moderately oversold. “That’s where we sit today.”

Although the price of oil has come a long way since February, when it bottomed at US$27 a barrel, Gervais believes it must rise to about US$60 a barrel so that energy producers’ balance sheets are repaired and high-yield investors can recoup their investments.

“We are halfway in the recovery to the median price [of oil], if you want to call it that. But as the industry tends to behave, we either overbuy or oversell. We’re going to go from oversell to likely overbuy,” says Gervais. “It would not surprise me if we pass US$60 a barrel and overdo it at US$75. That’s how the cycle works.”

Gervais has allocated about 51% of Mackenzie fund’s AUM to energy companies (including pipelines and equipment providers), 30% to metals and mining, with smaller holdings in chemicals and forest products.

One of the top positions in the 60-name Mackenzie fund is Devon Energy Corp., a major player in the U.S. shale-oil industry that produces about 700,000 BOE a day. “[Devon] has a second-tier management with first-tier assets,” says Gervais.

Assuming the energy cycle keeps moving upward, Gervais estimates that Devon stock, now trading at about US$35.90 ($45.20) a share, could be at US$48 within two years.

The rebound can be attributed largely to the recovery in commodities prices and recognition among market players that stocks were oversold, agrees Darren Lekkerkerker, portfolio manager at Toronto-based Fidelity Investments Canada ULC and portfolio co-manager (with Fidelity’s Joe Overdevest) of Fidelity Global Natural Resources Fund. “When stocks are oversold, [that] sets up conditions for a Lazarus-like rally,” says Lekkerkerker. “[Resources stocks] were oversold globally.”

The recovery of the gold bullion price, now at US$1,200 an ounce, was driven by a weakening U.S. dollar (US$), which trades inversely with the price of bullion, and the emergence of negative interest rate policies in jurisdictions such as Japan and Europe, says Lekkerkerker.

In the case of oil, the market is gradually adjusting to competing forces in the global industry, especially between the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and North American shale-oil producers.

“All these companies that had been doing so well [until the sudden decline in oil prices two years ago] will need time to bring on their new projects. You need time to see the effects of the change in behaviour to cut back on spending,” says Overdevest, noting that U.S. production is expected to drop to about 9.2 million barrels a day.

“At the same time, banks are extending less credit. When you do that, you accelerate the decline in spending and production.”

Is the worst behind us? Overdevest is reluctant to be definitive: “Certain ingredients are in place for supply and demand to become tighter. But we live in a very dynamic world. Many changes might happen. One of the biggest worries is that global [gross domestic product] slows down. Or, that the oil price moves up and companies spend too much money. But, in general, supply and demand is getting better. “

Overdevest and Lekkerkerker, who are bottom-up stock-pickers, have allocated about 56.2% of the Fidelity fund’s AUM to energy firms (including equipment makers) and 25.8% to materials (including precious metals and chemicals). There are smaller holdings in paper and forest products and about 10% in cash, which is deployed when stocks on the portfolio managers’ “buy” list become attractive.

On a geographical basis, Canada accounts for 51% of the Fidelity fund’s AUM; the U.S., 40%; and smaller positions in the U.K.

Overdevest and Lekkerkerker like firms such as Randgold Resources Ltd., a leading gold company in Africa that produces about 1.2 million ounces annually.

“[Randgold’s] thinking is: ‘We should be able to generate a 10% internal rate of return at a US$1,000 gold price’,” says Lekkerkerker. “That’s why these guys make money at US$1,200 an ounce. Or even last December, when gold was US$1,050 an ounce – whereas the rest of the industry was really struggling.”

Randgold’s Nasdaq-listed American depository receipts are trading at about US$83.50 ($105.20).

© 2016 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.