Slightly more than a year has passed since the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) threatened to shake up the country’s investment business with a pair of major policy initiatives: a proposed ban on deferred sales charges (DSCs) and a set of reforms to raise conduct standards (a.k.a. the client-focused reforms). After a tumultuous year, the status of those reforms is unclear.

In mid-September 2018, the CSA unveiled its long-awaited policy approach to investment fund fee structures. While that proposal disappointed investor advocates by stopping short of calling for the elimination of embedded compensation structures, it did take the more modest step of proposing to do away with DSCs and ban the payment of trailer fees to discount brokers (which don’t provide investors with advice).

Fast-forward to today, and advocates for investor protection are even more bereft. The CSA has yet to move forward on curbing the DSC as proposed a year ago, and there are few signs the regulator will do so any time soon. The proposed DSC ban isn’t officially dead, but it seems to be on life support, at best.

The Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) – Canada’s largest, most influential securities regulator – will state only that the DSC issue is still on that regulator’s agenda as part of the annual statement of priorities. In the 2019 statement, which set out the OSC’s annual policy agenda, the regulator pledged to work with the rest of the CSA to “develop responses” to the 2018 proposals in its current fiscal year, which ends in March 2020.

Louis Morisset, chair of the CSA and president and CEO of the Autorité des marchés financiers, offers a few more specifics: “The CSA is currently working toward finalizing its recommendations on the proposed reforms and next steps in collaboration with self-regulatory organizations.”

As for what those recommendations will entail – and whether they still will feature a DSC ban – Morisset says, “The CSA anticipates proposing rule changes to mitigate the conflict of interest and related investor harms arising from the use of the DSC purchase option.” He adds that the CSA also still intends to stop the practice of investment funds paying trailers to discount brokers.

Regarding the timing for these proposals, Morisset says the CSA expects to continue working on the next steps for DSC reform through the autumn. The CSA probably will take several months before it is ready to publish revised proposals.

The key challenge for the CSA, however, is Ontario’s provincial government, which hasn’t backed away from its opposition to a ban on DSCs.

A year ago, the CSA’s decision to ban DSCs was immediately thrown into disarray by the new provincial government in Ontario, which, in a highly unusual move, voiced its opposition to the CSA’s policy even as the regulator released its proposals. Since then, the Ontario government also has pushed the OSC to find ways of reducing regulatory red tape rather than lead the charge to step up investor protection.

When the Ontario’s government fired its shot across the bow of the CSA last year, the province nonetheless pledged to work with regulators to “explore potential alternatives” to a ban on DSCs. Yet, so far, no alternatives have been put forth by the government or regulators.

Keep in mind that moving to ban DSCs took the CSA almost six years. The regulator first outlined its concerns with embedded fee structures in a 2012 consultation paper. That was followed by extensive industry consultation and rigorous academic research that found embedded compensation structures harm investors. Further consultation followed before the CSA finally reached its decision to preserve trailers (except for trailers paid to discount brokers), but to eliminate DSCs.

Will devising a suitable alternative to eradicating DSCs, one that also addresses the regulators’ long-standing investor protection concerns, take another six years?

The prospect of that seems even less likely, given that, in the meantime, Ontario’s government also prompted the OSC to make regulatory burden reduction its top priority.

Shifting the OSC’s focus doesn’t necessarily equate to eroding investor protection, as the regulator stressed during its consultations on burden reduction initiatives. At the very least, however, the diversion of resources to the task of looking for ways to cut compliance costs inevitably reduces the OSC’s capacity to champion investor protection within the CSA.

Moreover, the Ontario government continues to demonstrate an unusually keen interest in the details of regulatory policy. Governments usually defer to financial services regulators on investment industry policy matters. But the current provincial government appears to be taking a more hands-on approach.

“Typically, governments don’t get significantly involved with regulators, as they view them as the experts in the field,” notes one investment industry veteran, who asked not to be named. “[That’s] not the case with this government.”

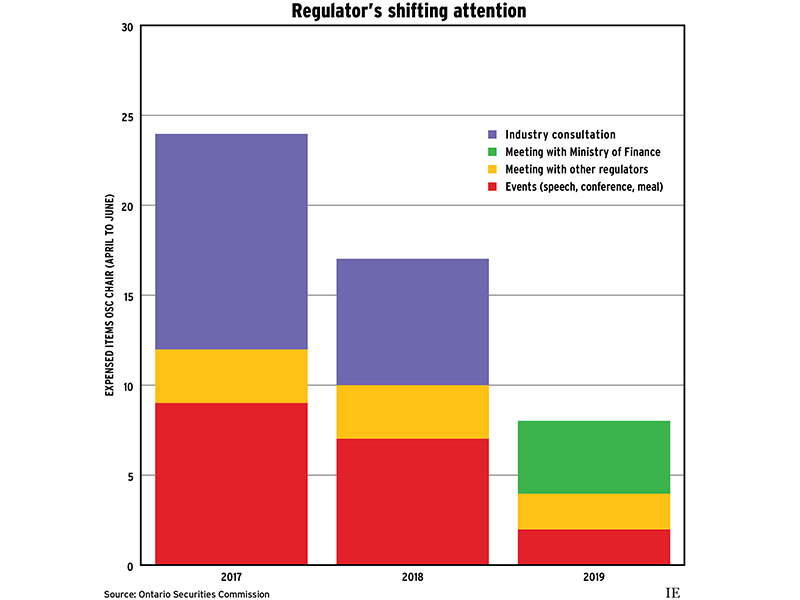

The belief that government involvement with regulatory policy in Ontario has ramped up is also reflected in the latest public expense reports of OSC chair Maureen Jensen.

Those reports show that from April to June this year, Jensen expensed eight items, half of which involved meetings with the provincial Ministry of Finance. There were no industry consultation meetings during this period or meetings with other stakeholders. The report also shows two industry events and two meetings with other regulators (the CSA and the International Organization of Securities Commissions) during the same period.

By comparison, in the corresponding quarter last year (before the current government in Ontario took office), Jensen’s expense report covered 17 items, but none were meetings with the Ministry of Finance. Instead, the quarter last year featured seven meetings marked as “industry consultations,” along with assorted regulatory meetings and various other functions, such as industry conferences.

Similarly, the expense report for the corresponding quarter in 2017 covers 24 events, including 12 industry consultations, various meetings with other regulators and other industry events – but, again, no meetings with the Ministry of Finance.

These expense reports reveal only a small slice of the regulator’s work, but they do point to a decisive shift over the past year: consultations with industry experts and other regulators now appear to be taking a back seat to meetings with the current government at the highest levels of the OSC.

Against this backdrop, there is also the question of the fate of the CSA’s other big policy project of 2018: the client-focused reforms.

These proposals, which were released several months in advance of the CSA’s proposed DSC policy, aim to improve industry conduct standards by revising the existing rules in several areas, including the rules on conflicts of interest, suitability, know-your-client requirements and know-your-product requirements. Among other things, the initial set of reforms also sought to introduce the “best interests” principles to the existing rules.

On that front, there is more hope that regulators will be able to make progress. Morisset says that the CSA was aiming to publish its revised proposals by the end of September.

However, there’s skepticism about the future for those proposals too. Industry sources indicate that the release of the revised client-focused reforms remains uncertain amid possible opposition from the Ontario government on this file as well.

The only thing that does seem certain at this point is that retail investors should not hold their breath in waiting for regulators to follow through on long-standing plans to beef up investor protection. The regulators’ concerns have not been resolved, and their ability to address them is being imperilled by politics.

Click the image below to download a full-size version of the chart.