In the bond business, investors’ rights are spelled out in covenants. Covenants, as part of the offering package for new issues, lay out such things as how much additional debt the issuing company may add after the bond is issued and the borrower’s obligations beyond paying interest on time and redeeming the bond at maturity.

Covenants can affect a bond’s quality. Sturdy covenants protecting investors raise the intrinsic value of a bond, while loose covenants with less investor protection reduce quality. The better the investor protection, the less risk the bond carries and the lower its interest rate needs be at the time of issue or trade.

Bond covenants can include debt restrictions. If there isn’t a covenant controlling debt, then the bond’s issuer can tap the market for, say, $1 billion, then do that again for another $1 billion next week or next month. Covenant limits on subsequent borrowing are reasonable, as are certain other limitations, such as debt to assets and debt to equity ratios, management prerogatives and dividend payouts.

Covenant sturdiness is an issue mostly in the U.S. In Canada, there has not been a move toward weaker covenants, says Tim O’Neil, managing director and head of Canadian structured finance for bond rater DBRS Ltd. in Toronto. “In this market, investors regard today’s covenants as acceptable. In Canada, to date, in structured finance, we have not seen many covenants weaken,” O’Neil says.

Most of the concern focuses on U.S. subprime debt, in which investor protection is eroding. But within that niche, the covenants’ tug of war is not just a boardroom debate on how much to promise bondholders. As Bloomberg LP reported on Feb. 20 this year, covenant strength is part of the recovery process during insolvency. Strong covenants mean recoveries in bankruptcy may be 70%; weak covenants can reduce that figure to 60% or as low as 10%.

Investor protection in the covenants of U.S. bonds and structured debt have weakened, says Vivek Verma, portfolio manager at Canso Investment Counsel Ltd. in Richmond Hill, Ont. Investors, eager for a return in today’s low-yield market, appear to be accepting weaker covenants – ones that offer little protection against more debt issuance, don’t put secured debt ahead of unsecured debt or don’t commit to maintaining debt or interest coverage at a certain level – in order to get a bit of extra return.

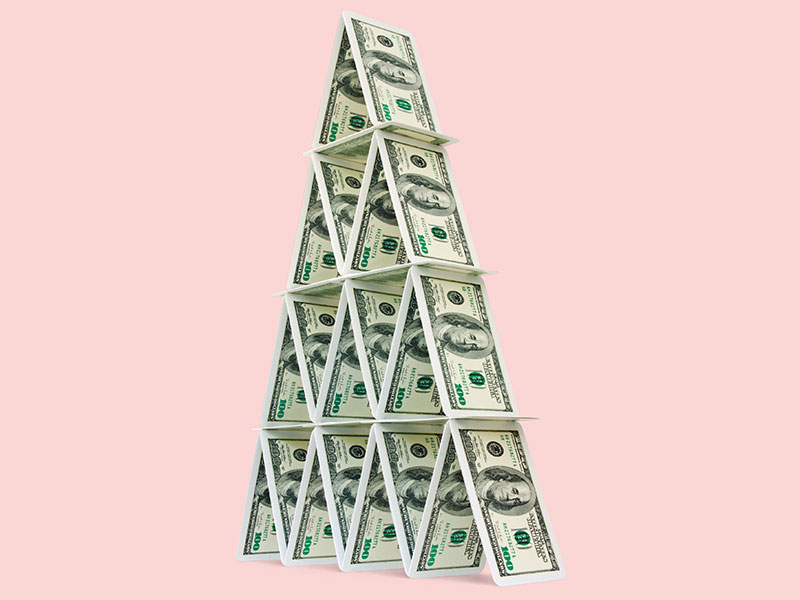

That investment strategy is a global trend, especially in structured finance such as collateralized debt obligations. In some cases, Verma says, “The [debt] market is so frothy that companies can issue bonds without covenants, so anything you can get is a bonus and is important.”

In 2010, 4.7% of U.S. issuance of leveraged debt had weak covenants, says John Laing, portfolio manager at Canso. In 2018, it was 87%, he notes. What should be investor preference for stronger covenants has also been weakened by fixed-income ETFs that purchase bonds without evaluating their investor protection. The ETFs buy bonds based on ratings and yield. Bond ETFs are put together, then issued to investors – often without an examination of any component’s covenants.

“Investors are looking to diversify risk and thus [are] not concerned about the structure of the [issue’s covenants],” Laing says. “The investors get the [asset] mix, but not necessarily the quality they may want.”

Recently, even more debt has gone “covenant lite” as highly leveraged companies draft rules that permit more incremental debt that pushes risk of non-payment of loans and non-recovery of the principal of issues in default ever higher, Laing adds.

The question now is: how far can the borrowing companies push down convenant quality before potential investors balk?

“Every extension of corporate obligations or increase in debt dilutes the value of a bond issued before the dilution,” says Chris Kresic, head of fixed-income and asset allocation at Jarislowsky Fraser Ltd. in Toronto.

May the investor beware.