Editor’s note: The plunge in the price of crude oil has repercussions not only for the broader Canadian stock market, but also for income-oriented investors. The fate of oil-company dividends was among the topics discussed at an equity-income roundtable, convened and moderated by Morningstar columnist Sonita Horvitch.

This three-part roundtable series continues on Wednesday and concludes on Friday.

The panellists:

Jason Gibbs, vice-president and portfolio manager at 1832 Asset Management LP. Gibbs is a senior member of the firm’s equity-income team, which has a wide range of mandates including Scotia Canadian Dividend, Scotia Income Advantage and Dynamic Global Infrastructure.

Michele Robitaille, managing director and equity-income specialist at Guardian LP, a sub-advisor to the BMO family of funds. The Guardian equity team’s mandates include BMO Growth & Income and BMO Monthly High Income II.

Peter Frost, senior vice-president and portfolio manager at AGF Investments Inc. His responsibilities include two income-oriented balanced funds: AGF Monthly High Income and AGF Traditional Income. He also manages AGF Canadian Stock, the firm’s domestic-equity flagship.

Q: The equity market is being dominated by concerns about the sharp fall in the oil price. Will this price recover any time soon?

Gibbs: There has been a fundamental shift in the oil market. For a number of years, oil had been trading between US$80 and US$100 a barrel. On Nov. 27, OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) made it clear that it would not be cutting its oil output. As a result, it could take quite a while for the oversupply to clear. There is still some production growth. It’s hard to predict the short term. Few people could have predicted six months ago that oil would fall below US$50 a barrel in January. Over time, you need a steady price of oil at US$65-plus per barrel for countries like Saudi Arabia or other OPEC nations to produce their budgetary surpluses or for the Canadian oil-sands to work.

Frost: U.S. monetary policy, with its quantitative-easing programs, has been a big factor in driving the pricing of bonds, equities and oil prices. Oil’s benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) price has responded positively to the introduction of a quantitative-easing program by the U.S. Federal Reserve Board. The Fed’s third quantitative-easing program was tapered down in 2014. It came to an end last October and, at that stage, WTI went straight down. The final skewer for the oil price was when OPEC decided to not defend the pricing in November. For me, the big factor will be Fed policy. Will the Fed increase its Fed funds rate in the first half of this year?

Robitaille: It’s a fundamental shift in the global oil market in that OPEC has, for the last number of years, been viewed as the balancing mechanism that has provided the price support for the commodity. OPEC has made it clear that it would leave it to market forces to address the oversupply situation, namely price. It’s a much messier way of balancing the market.

There hasn’t been a fundamental shift in the cost curve for oil. Natural gas in North America, by contrast, has seen this structural change in its cost curve with the advent of the Marcellus shale-gas play and cheaper drilling. The cost of getting oil out of the ground economically with a 10%-plus return is probably in the ballpark of US$75 to US$80. Oil needs to trend back up to that level.

Q: What is the outlook for interest rates? Will the fed raise its trend-setting short-term fed funds rate in 2015, as is widely expected?

Frost: I’m of the view that the Fed will not. Following the end of the Fed’s previous two quantitative-easing programs, you started to see weakness in the U.S. economy, with a lag of three to six months from the end of the program. But the Fed could surprise us and start to move rates up. This would flatten the yield curve substantially by increasing short-term rates. It would be hard for the financial sector, which does well in an upward-sloping yield-curve environment. Furthermore, bonds are showing us that we are in a deflationary environment in key parts of the world. Given all these considerations, the Fed might delay its interest-rate increases.

Gibbs: Yes. That could be one of the surprises for the financial markets this year.

Robitaille: I’m less certain that the Fed will not raise its rate. The United States is the one bright spot in the global economy. A big driver of the U.S. economy is the U.S. consumer. Things are going well for the consumer, with oil prices coming down and job numbers improving. You could see some strength in the U.S. economy that would be the impetus for the Fed to move the Fed funds rate above zero. It might want to go to 50 basis points; 100 basis points would be too aggressive.

Q: What will be the economic impact of lower oil prices on the United States and Canada?

Frost: There are likely to be large layoffs in the U.S. oil patch. Some of these jobs are high-paying and it’s hard to replace them in other sectors.

Robitaille: A lot of U.S. capital investment has been skewed to energy. So there’s a push and a pull to the strength of the U.S. economy. It’s not quite as clear-cut as a benefit to the U.S. consumer.

Frost: Energy is a more important sector in Canada and there will be more fallout. In addition to the adverse impact on the Canadian energy sector, there could be a reduction in the load factor of the airlines, which have been flying workers from the rest of Canada to and from the oil patch. It could also affect the volume growth of the railways, which have been transporting crude oil.

Robitaille: From a Canadian standpoint, it’s more uniformly negative. The west has been the growth engine of Canada for the last couple of years. In addition to the rails and the airlines, it could also impact the Canadian banks.

Q: What has been the response of the energy producers to the steep drop in the oil price?

Frost: The big focus of these companies is on protecting their balance sheets. That’s their number one priority. The companies are still committed to dividends. Will they have to cut their dividends, if the low oil price persists? Sure they will. Once the oil price moves up, they will be forthright in giving capital back to shareholders.

Gibbs: There have been indications that a number of companies will cut their capital expenditures. Some 15 or 16 companies have cut their dividends.

Robitaille: For example, Baytex Energy Corp. (TSX:BTE) has cut its dividend. Trilogy Energy Corp. (TSX:TET) has eliminated its dividend. The pace of the decline in oil prices has caught many companies by surprise. Some responded quickly with a dividend cut and this seems to have been prudent.

Q: What about the energy-infrastructure companies?

Frost: They have held in quite well. The pipeline companies were viewed as bond proxies for many years by investors searching for yield. Then the oil price fell and all of a sudden they became energy companies in the eyes of investors.

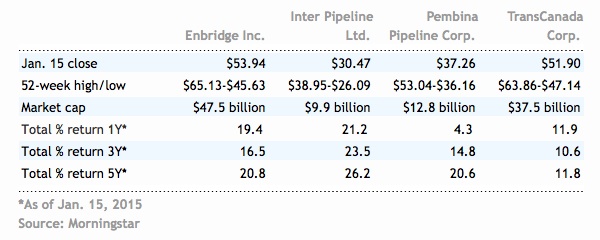

Gibbs: Some of the pipeline companies are more exposed to commodities, like a Gibson Energy Inc. (TSX:GEI), than others. Companies like TransCanada Corp. (TSX:TRP), Enbridge Inc. (TSX:ENB), Pembina Pipeline Corp. (TSX:PPL) and Inter Pipeline Ltd. (TSX:IPL) are fine for the next two or three years. Their projects are long-term and a lot of them are locked in. Also, the energy producers want access all over North America. It’s important for the long-term health of the business and that will not change. Looking forward, three years plus, you have to question the growth profile of these pipeline companies. It might not be as strong as it was in the past, as their customers have had an approximately 50% cut in their revenues.

Frost: I own major U.S. pipeline company, Kinder Morgan, Inc. (NYSE:KMI), which has held up fairly well. The company has stated that it’s looking to acquire, and some of the Canadian companies might be its targets.

Robitaille: Yes, particularly given the way that the Canadian dollar versus the U.S. dollar is going. A lot of these Canadian companies like Pembina and Keyera Corp. (TSX:KEY) have assets that are difficult to replicate. The growth in the demand for infrastructure assets will still be there, but the timelines for the projects will potentially be pushed out. With energy producers under so much pressure, a certain number of mid-stream assets are coming onto the market. Those mid-stream companies that are well positioned and have good balance sheets will have the opportunity to acquire. You have seen this with Keyera’s recent acquisitions.

Gibbs: A material change since our last equity-income roundtable in late 2013 is the regulatory, political blockages facing the pipeline companies. The Keystone XL, Energy East and Northern Gateway pipeline projects have all become such a political hot-button issue.

Robitaille: It’s taking longer and it costs more.

This three-part roundtable series continues on Wednesday and concludes on Friday.