With U.S. interest rates heading upward, the U.S. dollar (US$) should move downward. But will it? The consensus is the greenback is unlikely to rise much more, but won’t decline by much, either.

Those movements would be against the major currencies, the euro and the Japanese yen (¥). For Canadian investors, the Canadian dollar (C$) is what matters – and its value depends primarily on oil prices. No one is sure what oil prices are going to do, but the current betting is on some increase into the mid-US$40s-a-barrel range. That could bring the C$ up into the mid-US75¢ range from the US72.25¢ level at which the C$ ended 2015.

Such an increase would not be big. It would take a little off returns from U.S. investments when translated into C$, but probably is not enough to warrant hedging US$ exposure. If you or your clients think the C$ could get back up near US80¢, you might consider hedging.

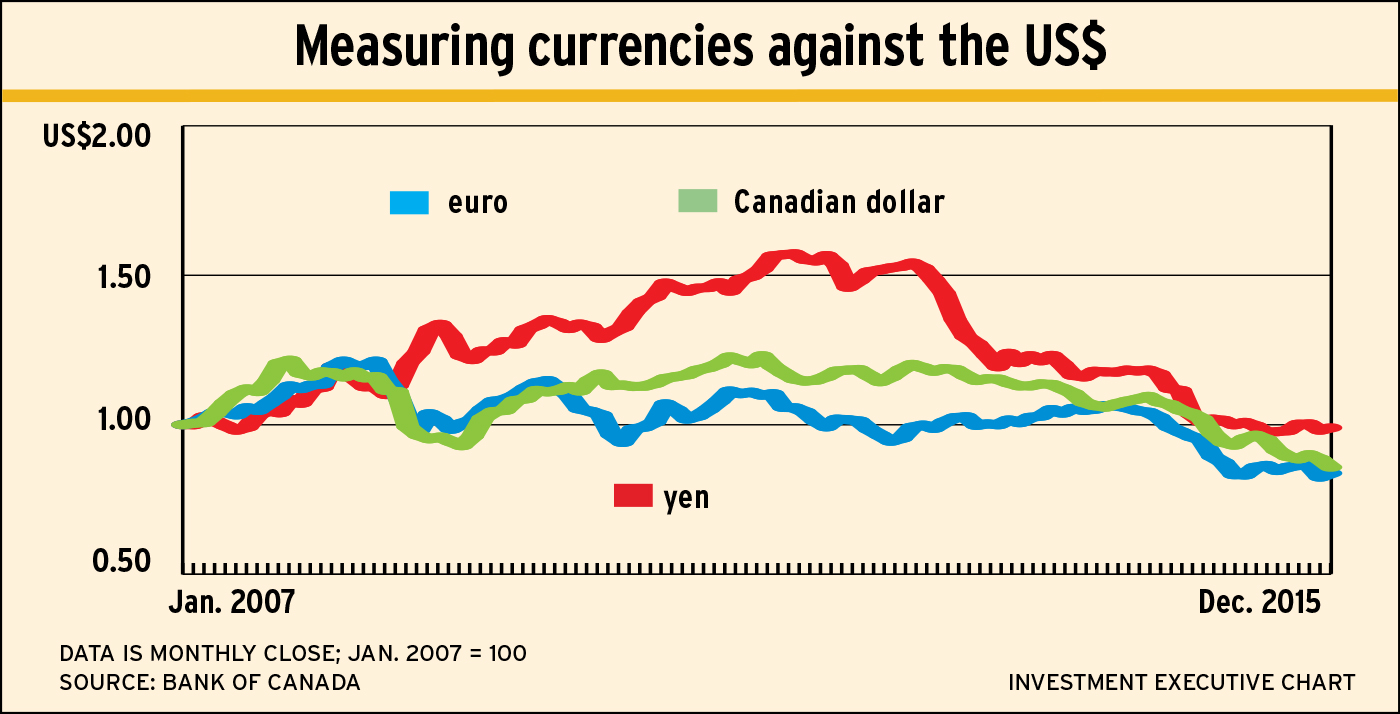

At the end of 2015, the C$ was down by 15.9% from a year earlier. The euro was also down, by 10%. But the ¥ didn’t move much, as it already had depreciated by 12.2% in 2014 and 17.6% in 2013.

For most countries, drops in the value of their currency vs the US$ is a good thing because that makes those countries’ goods and services more competitive in the U.S. market, to which most countries export, and makes home-produced goods and services more competitive against imports from the U.S. Lower currencies certainly were beneficial for Europe and Japan last year – and also for Canada.

But the US$’s strength is not a universal good. “Many emerging-market countries and companies have borrowed heavily in US$,” says Todd Mattina, chief economist and strategist, asset-allocation team, with Mackenzie Financial Corp. in Toronto. “As the US$ has gone up, it has become increasingly difficult to service that debt [in home currencies].”

Krishen Rangasamy, senior economist with National Bank of Canada in Montreal, agrees. He notes that US$10 trillion in US$-denominated debt is held outside the U.S., 40% of which is in emerging markets.

A strong US$ also is negative for commodity prices. Because oil, metals, gold, forest products and grains are priced in US$, demand is dampened in countries in which the currency’s value has dropped vs the US$.

This is not a problem in oil and metals because other factors – specifically, excess supply – have driven down commodity prices by far more than any currency-related impact. Indeed, the strength of the greenback is positive for non-U.S. commodity producers because they get more revenue when converted into their home currency.

As we head into 2016, the US$ is likely to remain around current levels against most currencies, says Ian Nakamoto, director of research at MacDougall MacDougall & MacTier Inc. in Toronto: “Most of the adjustment has been made.” He doubts the value of the euro or the ¥ will drop by more than 3% this year vs the US$.

Put another way, Drummond Brodeur, vice president, portfolio management, and global investment strategist with Signature Global Advisors, a unit of CI Investments Inc., in Toronto, believes the major central banks worked collaboratively to bring the euro and ¥ down – although they won’t admit it – and will watch carefully to make sure exchange rates stay near current levels.

However, that doesn’t preclude some ups or downs. For example, Charles Burbeck, co-head of global equity portfolios at UBS Global Asset Management (U.K.) Ltd. in London,U.K., thinks the euro could rise by 5%-10% against the US$ in the next two to three years.

Much further decline in the ¥ is unlikely – but so is much appreciation. Japan’s government seems happy with the current level of the ¥ and many strategists, including Mattina, think that is why the Bank of Japan has decided not to increase quantitative easing, which was a major factor in the ¥’s depreciation in 2013 and 2014.

China’s renminbi is a different kettle of fish. That country’s authorities are trying to move the renminbi gradually to a free-floating currency. An important step was getting it recognized by the International Monetary Fund, which now includes the renminbi in the IMF reserve pool, known as the Special Drawing Right, along with the US$, the euro, the yen and the British pound.

In the meantime, China is trying to depreciate the renminbi to increase the competitiveness of the country’s exports, but that would have to be done slowly – as indicated by the negative market reaction to a 2% decline in the currency last August.

© 2016 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.