Few would disagree that it makes sense to invest globally. Where views differ is on how best to go about it, and how to define diversification.

According to conventional thinking, geographic diversity is based on where the company is domiciled. That’s the process by which fund-measurement firms, including Morningstar, collectively determine fund categories in Canada. The Emerging Markets Equity category, for instance, consists of funds that invest at least 90% of their equity holdings in in a broadly based portfolio of securities from emerging-markets countries.

There’s another school of thought as to what constitutes going global. It holds that what matters most in diversifying geographically is where a company earns its revenues, as opposed to where its head office is located or on what exchange its stock is traded.

Among other things, this reinvention of the concept of global investing attaches greater importance to having exposure to emerging markets, whose growing economic heft has far outpaced the stock-market capitalizations of companies domiciled in these countries.

Conversely, more mature markets such as the U.S. and Europe have stock-market capitalizations that are disproportionately high in relation to their domestic or regional economies.

However, revenue-based global investing takes into account the global reach of multinational companies. In fact, multinationals based in developed markets may be among the best ways to obtain exposure to fast-growing developing markets.

One of the most avid proponents of a revenue-driven approach to geographic diversification is the fund-management giant Capital Group Companies Inc. The company has trademarked a name for it: The New Geography of Investing.

Portfolio managers and research analysts who analyze companies have always been aware that multinationals do some or even most of their business outside the countries where they’re domiciled.

A much more recent development is the growing availability of company data to enable revenues for an entire universe of stocks to be tracked by country or region. “For many years, that data was quite difficult to come by,” David Polak, a New York-based equity specialist with Capital Group, told Morningstar.

Capital Group relies on data compiled by MSCI for its analysis of revenues by country and region. Polak says roughly two-thirds of companies whose shares are constituents of the MSCI All Country World Index (MSCI ACWI) provide country-by-country revenue data, while the remaining companies provide regional breakdowns.

Capital Group contends that a company’s domicile generally provides little information about its potential success or its future stock price. Far more meaningful is a company’s economic exposure, with revenues as the best available measure.

As Capital Group’s strategists and portfolio managers acknowledge, there are exceptions to this rule and location hasn’t become irrelevant. In some instances, a country’s macroeconomic or geopolitical situation may become overriding concerns. (In this context, Russia comes to mind, with its equity and bond markets having plunged in response to its shrinking oil-export revenues and economic sanctions imposed in response to its military actions in Ukraine.)

Such exceptions aside, economic exposure by country is normally a far more important determinant of equity returns. It’s a more accurate mapping of current and prospective global investment opportunities.

When geographic allocation is based on the traditional approach of where companies are incorporated, fast-growing emerging markets tend to be downplayed. As of Dec. 31, emerging-markets companies constituted 10.3% of the MSCI AWCI as defined by their domiciles and their market capitalization. But in terms of their share of the all-country revenue pie, emerging-markets countries soar to a 28% weighting of the index.

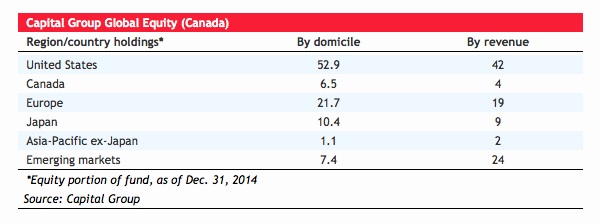

Emerging-markets exposure can also be measured for individual mutual funds or exchange-traded funds. For instance, Capital Group Global Equity (Canada) held just 7.4% in emerging-markets stocks in its equity portfolio at the end of December. But the fund’s exposure to that same region by revenue was 24%, more than three times higher.

Conversely, 52.9% of the Capital Group fund’s equities were domiciled in the United States, versus only 42% U.S. exposure when measured by where companies earned their revenues.

For investors who hold individual stocks directly, revenue-based analysis sheds light on geographic exposure. For example, consider the Danish-based pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, which is a global leader in drugs to treat diabetes and is among the top current holdings of Capital Group Global Equity.

According to third-quarter 2014 data provided by Capital Group, Novo Nordisk is very much a global company. Only 22% of its revenue was from sales in Europe, its home base. This was less than the 24.8% that came from emerging markets. The largest portion of Novo Nordisk revenue, 42%, was from customers in the U.S., the world’s biggest spender on health care.

Similarly, the global software giant Microsoft Corp. (Nasdaq:MSFT) — which is based in suburban Seattle and earns roughly half of its revenue in its U.S. homeland — is also a significant play on emerging markets. Microsoft, another top holding in Capital Group’s retail global fund in Canada, earned 27.5% of its revenue from sales in emerging markets. That’s more than it earned from Europe and Japan combined.

Back in the early 1990s, says Capital Group’s Polak, roughly two-thirds of the performance of emerging markets was attributable to country and industry-sector factors.

Over time, he adds, company-specific factors have become more important. “We think the spirit of emerging-markets investing is to invest in faster growing companies.” By that, he means taking a revenue-based approach to global investing.

On the basis of both revenues and domiciles, companies like the Brazilian beverage company Ambev SA and India’s leading automaker Tata Motors Ltd. are clearly plays on emerging markets. Capital Group’s New Geography serves to remind us that so too are developed-markets multinationals like Novo Nordisk and Microsoft.